As the ocean air spritzes my face on a late morning this past June, its saltiness meets the saltiness of the hot tears rolling underneath my tortoise-rimmed sunglasses. Almost a year has passed since I’ve stood in this very place, on the deck of a family friend’s beachfront home at Davis Park, one of the easternmost seaside communities on Fire Island. Part of the U.S. National Park Service’s Fire Island National Seashore, this 32-mile-long, quarter-mile-wide barrier island protects the south shore of Long Island, New York, from the Atlantic Ocean. But this time, I stand here betrayed by the person who was supposed to protect me.

Fenced in by sand-trapping wooden slats wired together, the wispy beachgrass wavers in the wind. Away from the coastline, the long blades form an almost-continuous carpet of green, with only a few bald spots where the sand peeks through. But closer to the ocean’s edge, the vegetation is not as well-colonized; sprouts surface from the sand in staggered rows. Underground, the plants will form a dense network of stems, which will spread horizontally up to ten feet each year. When nature buries the plants alive in sand, the underground stems will send new shoots vertically to the dune surface. Beachgrass is hardy, highly tolerant of salt spray, direct sunlight, extreme heat, and drying winds. Though beachgrass has adapted to life in a tough environment, it can’t withstand trampling by vehicles or pedestrians. A red sign reading “KEEP OFF DUNES” warns beachgoers of its fragility. Without vegetation like beachgrass holding sand in place and keeping the dune together, inland areas become more vulnerable to coastal storms and other extreme weather events.

At least once every summer, I hop aboard a ferry across the Great South Bay to this respite from modern life. Upon disembarking, I am immediately transported to a simpler place. Congested roads give way to a maze of elevated wooden walkways forming avenues, streets, and alleys. The constant whooshing of cars passing by and honking of horns by traffic-agitated drivers are replaced by lightly treading bicycles and pull carts toting luggage, groceries, beach gear, and children. Beyond the marina, no lights line the streets; at nighttime, the stars dazzle like fireflies in a dark sky.

But instead of the tapestry of multicolor umbrellas I typically see planted across the sand, only two side-by-side chairs sit near the ocean’s edge. The strip of white-quartz sand sprinkled with colored minerals is remarkably narrower than I remember in years’ past. Maybe ten feet at most separates sea from inland.

Coastal landscapes are ever-evolving. Natural forces—winds, waves, currents, and tides—and human activity continually shape and reshape the landscape. Changes to coastal environments can occur rapidly due to storms or gradually over seasons and annual cycles. Acutely aware of the instability of such a dynamic system as Fire Island, especially in the face of climate change and rising sea levels, government officials have instituted measures to help curtail erosion. One such measure is beach nourishment, in which sand is dredged from offshore locations and pumped onto the beach. While sand dunes have helped absorb the impact of major storms over the years, they require regular replenishment to counteract the removal of sediment. For example, after a 2007 nor’easter, nearly 26,000 cubic yards of sand was added to Davis Park beaches. By the following year, an estimated 30 to 40 percent had been lost to erosion. In 2012, Superstorm Sandy swept away more than half of Fire Island’s beaches and protective dunes. Today, the barrier island continues to rebuild. A multi-billion-dollar project sponsored by federal, state, and local partners to protect the 83 miles of coastline from the Fire Island Inlet to Montauk Point at the tip of Long Island is expected to begin next year.

As I watch the waves roll onto the shore, I begin to process how, like the beach, the relationship between me and my husband has eroded.

Erosion means . . .

1. the act or state of eroding; state of being eroded.

2. the process by which the surface of the earth is worn away by the action of water, glaciers, winds, waves, etc.

3. the gradual decline or disintegration of something.

Our relationship falls into the third definition. The night before my trip to Davis Park, we ended our eight-year relationship. A month earlier, days after celebrating our second wedding anniversary, he told me he was unhappy in our marriage.

“It’s really serious,” he said glassy eyed one night on the couch while we watched Netflix, after I sensed he was disengaged and prodded him to share what was on his mind. “Something is missing with us. We don’t laugh anymore. We don’t have fun anymore. I’m bored.”

Over the last few months, I had noticed changes in my husband’s behavior. He had become more consumed by his anger. Besides punching through walls and throwing objects, he would yell at me for trivial things. If I didn’t perfectly relay GPS directions to him while he was driving, he’d rip the phone right out of my hands. When I managed to book him a COVID-19 vaccine when appointments were scarce, he scolded me for the inconvenience I caused him. Almost every day after work, I would prepare dinner by myself, calling him into the kitchen when it was time to eat. On multiple occasions, he complained that dinner was ready before his self-employed workday ended. “Don’t you know I work until 6 p.m.?” he would exclaim, as if he ever had a set schedule.

Any time our boxer puppy incessantly barked at passersby from our five-panel bay window, my husband would spiral into a fit of rage, emerging from his office and stomping into our living room to hand him a backside strike. At any moment, a work email or phone call could set him off, sending him into a bad mood for the rest of the day. On most weekdays, he, the former college sprinter, didn’t even step foot outside. Each night, I would go to bed, and he would remain in his office with the door closed, playing video games for hours on end. Sometimes I would awake in the middle of the night to him crawling into the cold spot beside me. I couldn’t remember the last time he had asked me out on a date or to visit one of our favorite spots in nature. Or went out of his way to do something special for me. We were acting more like roommates than husband and wife.

One evening, I looked at him across the dining room table. “Is everything okay?” I asked, as I had many times before when I sensed he was agitated. “Yes,” he assured me. The sullen expression on his face said otherwise. But never once did I think it was us. I simply figured he was under an intense amount of stress. In January, he had started his own real estate investment company. The potential reward was high, but so was the risk. One failed deal on an apartment building could put us in debt hundreds of thousands of dollars, leading to our financial demise and the end of his career.

I explained how his personal issues had been affecting us, how by prioritizing his new business he had been neglecting me. But he was convinced his unhappiness stemmed from our relationship. I suggested we try to nourish our marriage through counseling, and he agreed. After only two sessions with two different therapists and a weeklong trial separation, I could tell his mind was already made up. The man with whom I had built a home saw this unhappiness as long-lasting. I thought we were resilient like the beachgrass, persisting no matter how much life tried to bury us alive. Seeing his doomed-to-fail mentality, I knew it was the end.

But standing there on the deck at Davis Park, overlooking the almost-nonexistent beach, I began to think about how people are ever-evolving, too. Life experiences continually shape and reshape us.

Maybe our relationship had been disintegrating for some time. Maybe life had worn us down since we met in our mid-twenties and entered our thirties, perpetually pounding us like the wind and waves. Our early days of long distance, with him traveling to Boston on the weekends to see me after a five-hour daily commute from the Hamptons to New York City. His move to Boston after finally landing a job, only to have the company go bankrupt a few months later. Our move from Massachusetts back to our home state of New York, where we traded alone time for family time. Living with my parents for three years while we saved up for a house. My family finding out about my dad’s secret adoption after nearly 60 years and navigating through new relationships with biological relatives. My breast cancer diagnosis at 27 and ensuing chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation. Making the decision as boyfriend and girlfriend to freeze embryos together in case chemotherapy rendered me infertile. His periods of job hopping and unemployment. A domino effect of deaths: losing four grandparents to deteriorating health and a relative and long-time friend to overdose. Renovating and renting a 1968 fixer upper we purchased as both a home and investment opportunity. Cancelling our honeymoon adventure to South Africa because of the pandemic. His risky business venture. Being cooped up during lockdown.

Ultimately, coastal erosion occurs because the supply of sand to the beach cannot keep up with the loss of sand to the ocean. Had our supply of love to one another become unable to keep up with our loss of enjoyment to health issues, career setbacks, deaths, and other life stressors? Could we no longer nourish our relationship, building it back up to the place it had once been?

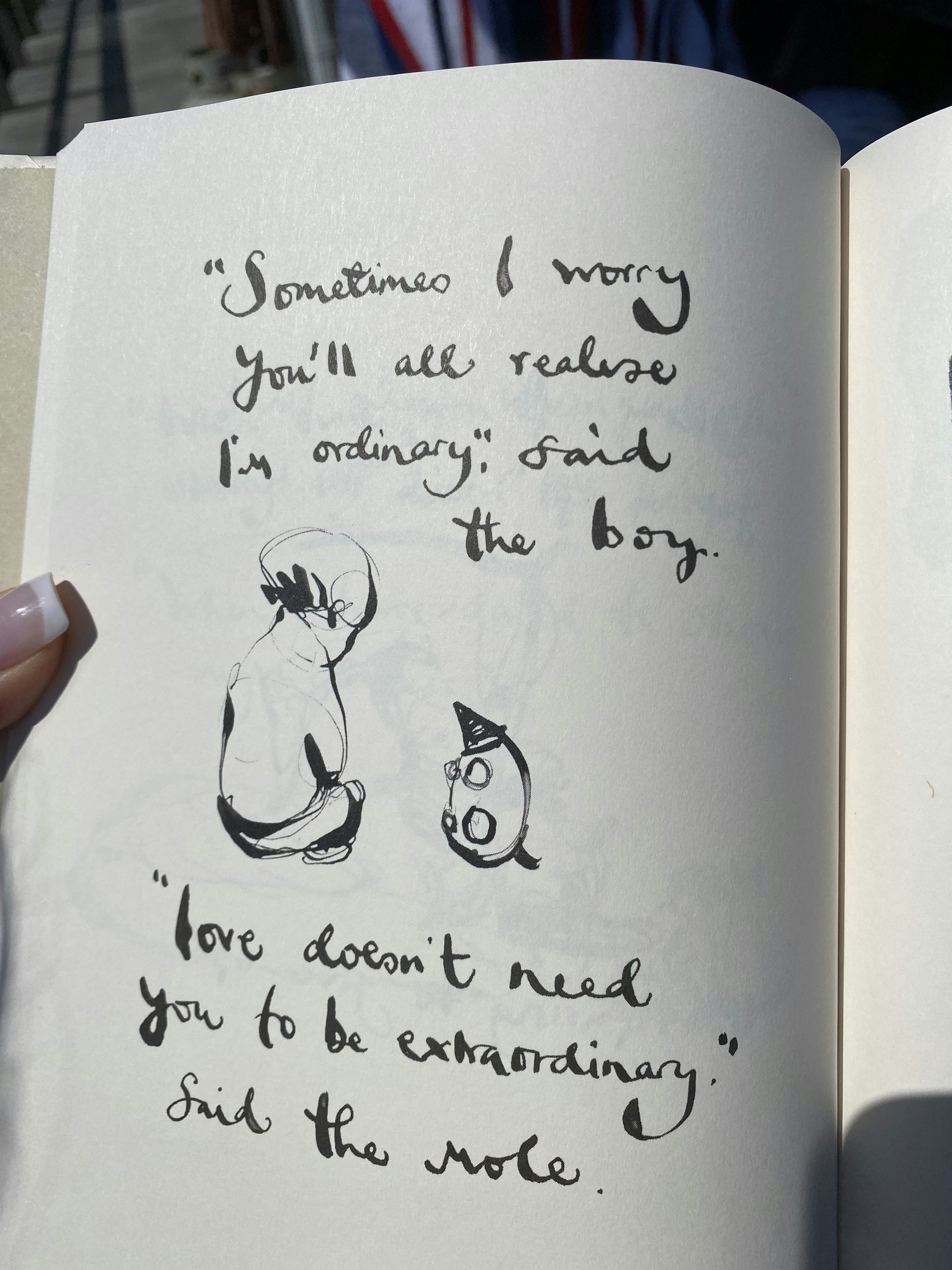

Later that afternoon, our host Nina—a clairvoyant, spiritual woman with a calming presence—sits beside me to chat. “You are welcome here any time. The beach is a place of healing. Here, I have something for you,” she says in her South American accent. She hands me The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse and tells me to place one hand on the top of the book, the other on the bottom. “When you are ready, turn to a page, and you will find a message meant for you.”

I wait a couple of seconds before cracking open the hardcover. On the page is an illustration of a boy and a mole, with dialogue: “Sometimes I worry you’ll all realise I’m ordinary,” said the boy. “Love doesn’t need you to be extraordinary,” said the mole. Reading these words, I realized I had fought the erosion long enough. It was time to let go, to let nature take its course. My love wasn’t and would never be adequate. No amount of nourishment could salvage this beach.

Toward the end of the day, I hear excitement among the other guests, who have spotted a whale surfacing to breathe. I rush over to witness this rare sighting, just in time to catch the plume of mist shooting from its blowhole. As we all stand together enamored by this magical creature in this magical place reminiscent of simpler times, I begin to breathe, too.

Ariana Tantillo is a science writer whose career has spanned two national laboratories: the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory and U.S. Department of Defense’s MIT Lincoln Laboratory. She is a graduate of Providence College with degrees in biology and English and is completing her master’s in science writing at Johns Hopkins University.

Discover more from Ariana Tantillo.