In the seventh issue of Clerestory Magazine, contributors locate places of rest and refuge.

Listen to this issue’s playlist on Spotify.

Dear Reader,

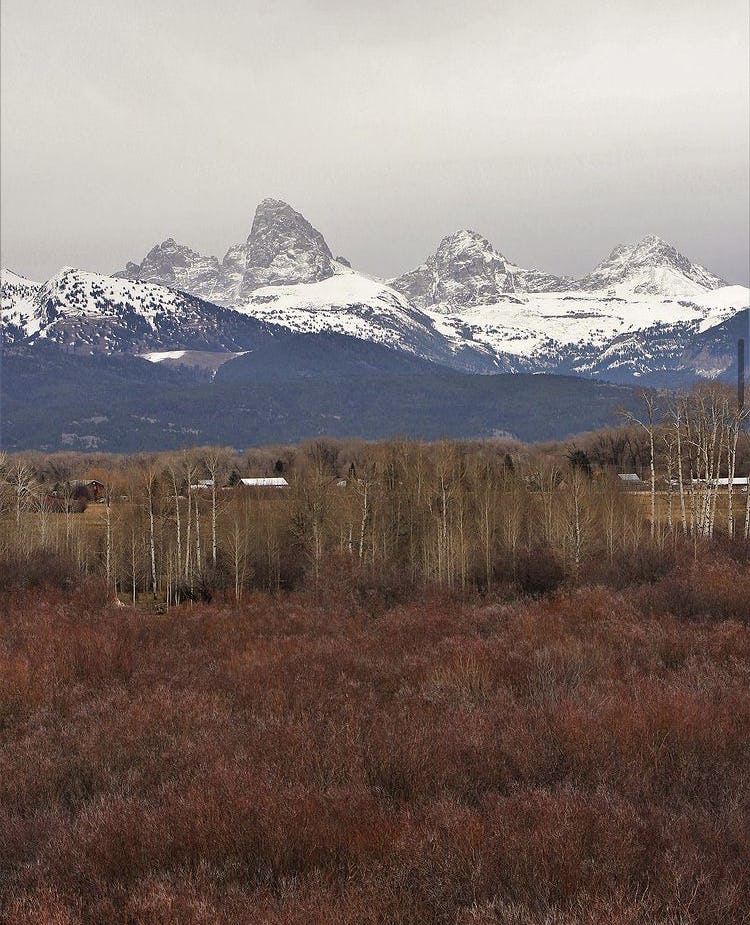

Many years ago, I spent twilight in the Vermont woods. The ink colored, centuries-old trees stretched above me toward the watercolor sky. The rustling of leaves, a sound almost like ocean waves, soothed me. I remember feeling at once supported and humbled: encased by nature’s healing force, like a kind of love, and also hyper aware of my smallness. What lives had these trees witnessed? Who else had laid their spine, like a string of pearls, on the soft earth? Saturated by peace, I felt free.

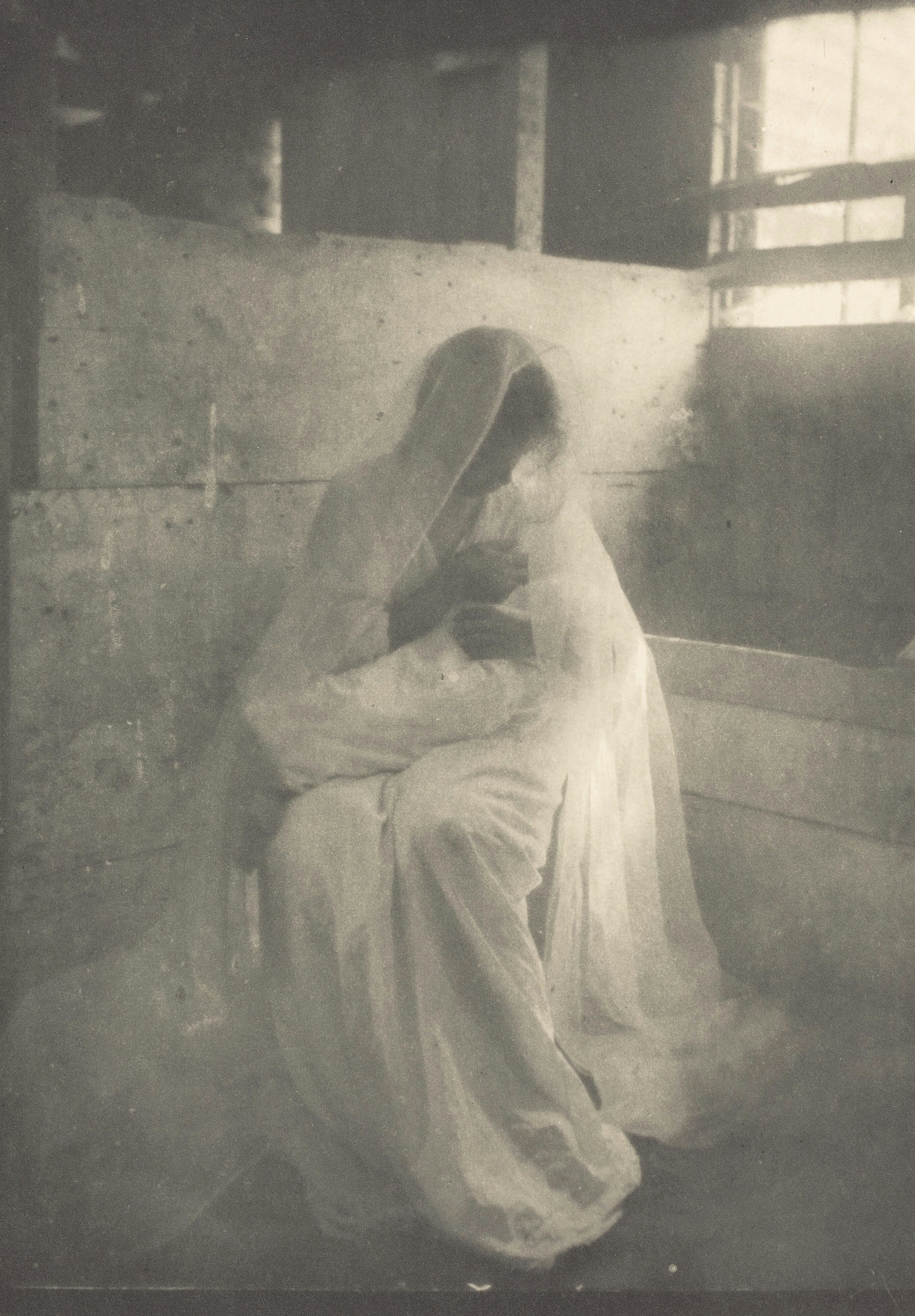

The root of the word sanctuary is sanctuarium, meaning “holy place.” Holy places are sites of restoration, where we can retreat and emerge renewed –with fresh eyes and clear hearts, quiet minds and bodies at ease.

In some ways, all of Clerestory’s work is about sanctuary. We draw our name from cathedral architecture. In our photography and writing, we call attention to the holy places of pain, grief, longing, and love. In our conversations, we highlight vital work on healing, compassion, and the common good. And in our sharing these stories, we hope to provide a brief respite from our violent and dehumanized world, a kind of online sanctuary where we receive the wisdom of others with openness and grace. This is an apt time to focus on sanctuary because, frankly, we need it. We need more maps to healing and wholeness, to rest and contemplation.

The church my family attended when I was a child had the word “sanctuary” written on the threshold into the chapel space. Church, though, was not a sanctuary for me, but rather, a stifling place I was required to be, with theology and social teachings that enraged me. I am not alone in this experience of organized religion. As the Pew Research Center reports, Christianity, along with "churchgoing habits," is swiftly declining in the United States. For good reasons, many of us have left the restrictive faiths of our upbringings, but in the process, we have lost shared spaces for gathering with our neighbors, shared language for understanding everything from social responsibility to grief, and shared practices, or rituals, which bring us comfort.

It also bears mentioning that shared spaces in the United States, like schools, temples, chapels, grocery stores, community centers, and main streets have been the sites of massacres and gun violence in recent months. That horror and hatred so regularly pervade places dedicated to learning, community, and prayer is devastating.

Where do we gather to share joy and sorrow? Where do we shelter each other? How can we create spaces of sanctuary for ourselves and others? How can we build more loving relationships with our bodies? Why are holy spaces important? These are just a few of the questions our contributors will pose and respond to this season.

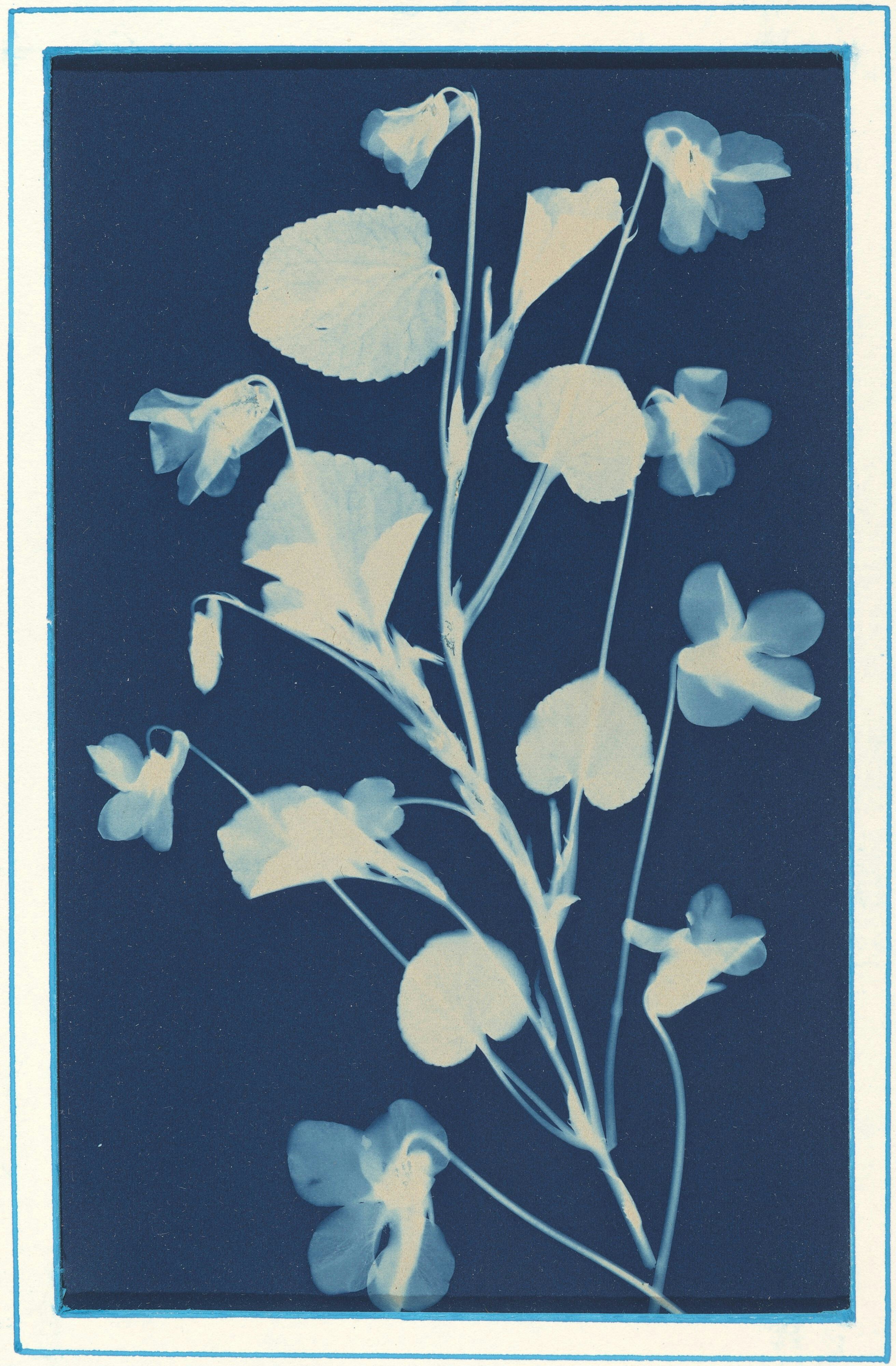

As we begin the fall, let me leave you with Mary Oliver’s “Song for Autumn,” a lovely meditation on sanctuary.

Don’t you imagine the leaves dream now

how comfortable it will be to touch

the earth instead of the

nothingness of air and the endless

freshets of wind? And don’t you think

the trees themselves, especially those with

mossy hollows are beginning to look for

the birds that will come — six, a dozen — to sleep

inside their bodies? And don’t you hear

the goldenrod whispering goodbye,

the everlasting being crowned with the first

tuffets of snow? The pond

stiffens and the white field over which

the fox runs so quickly brings out

its blue shadows. And the wind wags

its many tails And in the evening

the piled firewood shifts a little,

longing to be on its way.

Warmly,

Sarah James

Editor-in-Chief

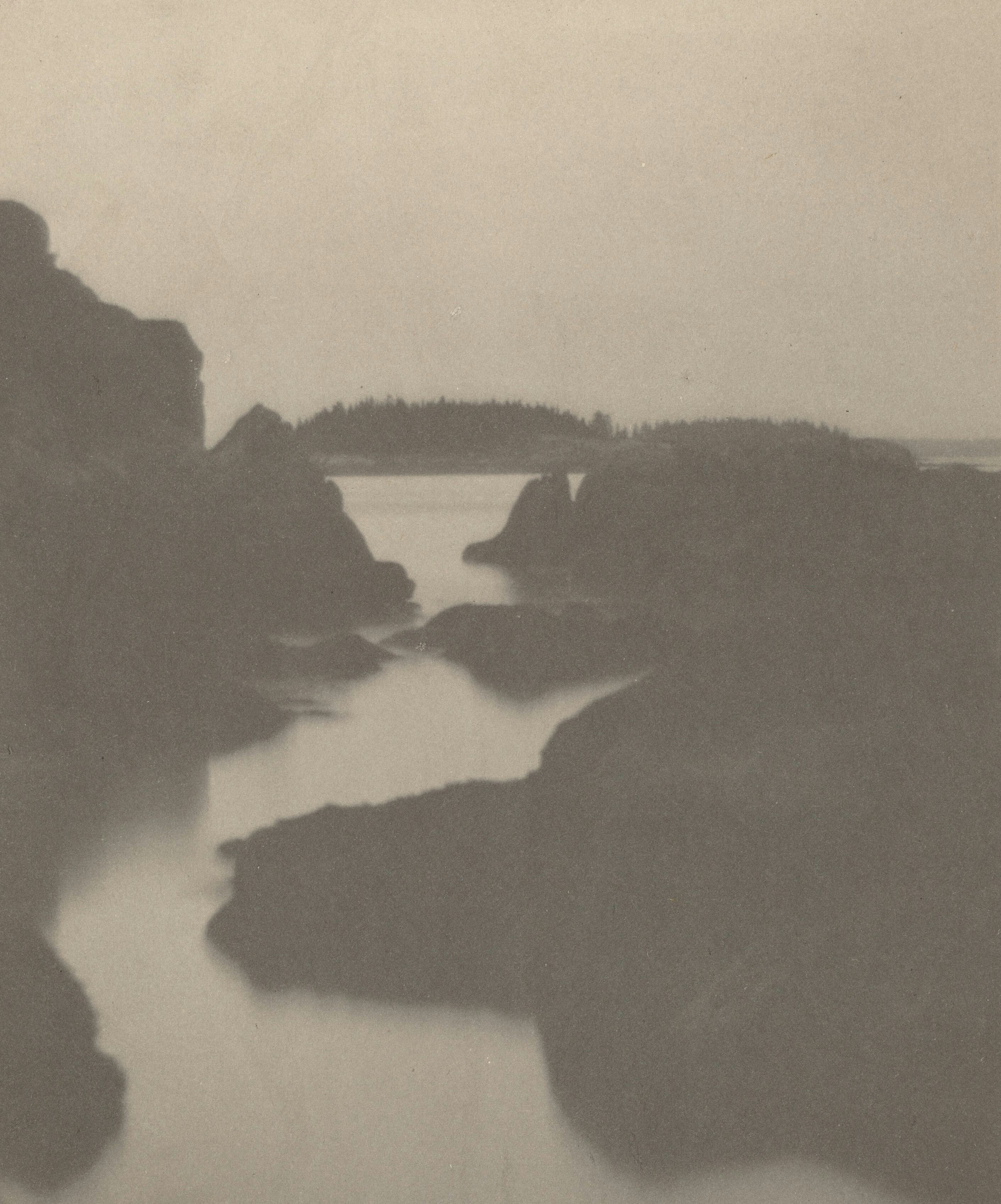

Issue cover photo credit: Marte Marie Forsberg

Sarah James is the editor-in-chief and founder of Clerestory Magazine.

Discover more from Sarah James.

.jpg?ixlib=gatsbyFP&auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=max&q=50&w=8256&h=5504)

.jpg?ixlib=gatsbyFP&auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=max&q=50&w=6192&h=8256)

.jpg?ixlib=gatsbyFP&auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=max&q=50&w=3676&h=2879)

.jpg?ixlib=gatsbyFP&auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=max&q=50&w=3750&h=3750)

.jpeg?ixlib=gatsbyFP&auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=max&q=50&rect=55%2C0%2C875%2C640&w=875&h=640)

.jpg?ixlib=gatsbyFP&auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=max&q=50&rect=0%2C1196%2C6192%2C7056&w=6192&h=7056)