In the fourth issue of Clerestory Magazine, writers explore the environment and relationality.

Listen to this issue’s playlist on Spotify.

Dear Reader,

In response to the most-recent report from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, The New York Times wrote, "A hotter future is certain.” The irreversibility of climate change is striking, but by no means surprising. Scientists, journalists, and activists, alike, have been warning us for decades of the totalizing and catastrophic impact of rising temperatures and greenhouse gas emissions. We live on a planet, what Bill McKibben called “Eaarth” nearly a decade ago, which is irrevocably damaged and shaped by destruction.

How do we locate ourselves within a dying world? What are our collective responsibilities as our planet changes and the most vulnerable among us are affected by heat, natural disaster, and displacement? What must change in order to save what is left of the planet we inherited? These are only a few of the questions Clerestory Magazine contributors will ask in our fourth issue on “ecology.”

In our summer issue, we responded to the prompt, “what heals?” This time around, we're asking : what connects? How are we connected to each other and the natural world? How can we nurture relationships which are life-giving and life-protecting? And how can we build a world that is founded on relationality, instead of on division and subjugation?

Ecology means “the relationship of living things to their environment and to each other.”

Most of us live in cultures founded not on relationality, but rather, driven by extractive capitalism and toxic masculinity as expressed in "power over," or "dominion over," paradigms - paradigms which led to genocide against indigenous people, violence against women, and the utter destruction of natural, life-sustaining ecosystems. Climate change makes it clear – these systems of violence, extraction, and destruction are unsustainable. They’re killing all of us.

It strikes me, that on a global cultural level, we’re learning many difficult and painful lessons about interconnectedness. The principle we’ve long ignored – that our “humanity is bound up” in each other’s, to borrow Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s words – is urgently and loudly expressing itself. We share the same resources. Our actions affect others. We are responsible for each other.

The COVID-19 global pandemic centered interconnectedness. We became frighteningly and precisely aware of how we share the same air, how our actions affect the health of our neighbors and loved ones. Right now, I can conjure images of how aerosol particles move through a classroom or an airplane. While there were waves of collective insight into human compassion and consideration, the pandemic revealed and deepened inequality. Some of us, were and still are, more at risk than others. The more resources you have, the less at risk you are. We know how this plays out in unequal access to vaccines or protective equipment, unequal distribution of space within which to social distance, unequal resources which determine every decision, from sending one's children to school to going to the grocery store.

Our ecological crisis, too, reveals interconnectedness. Rising global temperatures leads to rising sea levels leads to hurricanes with more damaging storm surges, for example. Or, on the flip side, biodiversity reveals the intricacy and majesty of ecosystems. In recent weeks, vulnerable communities have weathered extreme heat, wildfires, hurricanes, and flooding. Climate change and environmental degradation - manifest in the inability to evacuate before a hurricane to contaminated water - disproportionately affect low income communities, Majority World countries, and communities of color.

In exploring the meaning of place, in examining intersectional justice and environmental racism, in thinking relationally, I believe we can cultivate more compassionate hearts and act more mindful, sustainable ways. As Dr. Vandana Shiva reminds us, "In nature's economy, the currency is not money, but life."

Gary Snyder, in "For the Children," writes:

The rising hills, the slopes,

of statistics

lie before us.

the steep climb of everything, going up,

up, as we all

go down.

In the next century

or the one beyond that,

they say, are valleys,

pastures,

we can meet there in peace

if we make it.

To climb these coming crests

one word to you, to

you and your children:

stay together

learn the flowers

go light.

Stay together, learn the flowers, go light. This is good advice for living purposefully in a dying and uncertain world. Thinking and acting relationally demands a lot of us. It asks that we pay close attention to the suffering of other living beings. It is a more painful, and yet more beautiful way to live. It offers hope for a different kind of world, with flourishing, dignity, and connection at the center.

Over the next three months, Clerestory writers will explore place, the meaning of “nature,” environmental history, climate grief, and what is needed to restore and sustain relationships, between us and between us and other living things. As we undertake this important work, you may find our reading list with further suggestions on ecology here.

Thank you for being here.

Best wishes,

Sarah James

Founder and Editor-in-Chief

Clerestory Magazine

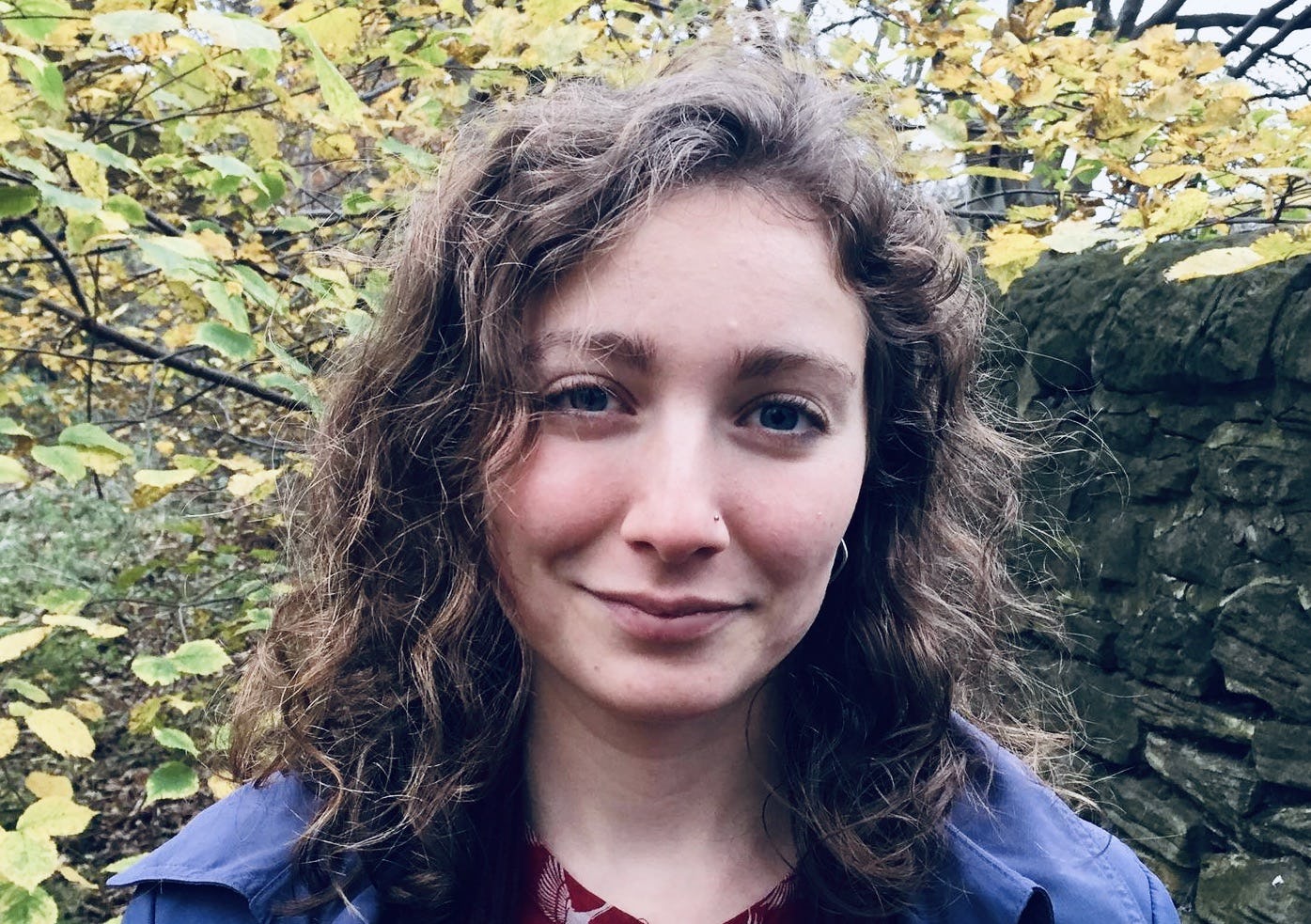

Sarah James is the editor-in-chief and founder of Clerestory Magazine.

Discover more from Sarah James.