When your dad drops you off at school this morning and reminds you that he has signed you up for the cross-country team, you wonder how you got roped into this one.

One of my earliest memories of coming to terms with mortality was when I was a child, just shy of seven years old.

Some time ago, I went to a reading by an excellent Midwestern poet.

It was summer; and there was a patchiness to the weather.

On our walk through town, my husband and I passed by an assisted living facility. There were a couple dump trucks in front.

Somewhere in a hotel gym, a mother is running on a treadmill. Her sneakers haven’t touched pavement in months, and her taupe leggings make her thighs look like seals.

Spring in our county brings wind. Early in the morning, a light breeze lifts leaves on the trees, in and around the back patio.

When I see the three positive pregnancy tests lined up on my bathroom counter, my first thought is that I wanted another baby, but I did not want another baby like this.

The mind plays tricks on us. This we know. The heart is deceitful above all things. This we accept. But the body is the consummate con artist.

What does it mean to make your body a home when all it has ever known is the loud incessant chatter of rooms too full of thoughts so mean, you’d only dare say them to yourself?

In 1330, five days after he killed his wife, Geoffrey of Knuston of Abingdon sought sanctuary in a church in Northamptonshire.

I used to think that my hometown would always feel welcoming, that I would always be able to slide back into place. I plotted my return for many years.

It is common to intellectualize the sacrament of Communion, and to view the practice as a sacred ritual of reverence.

I am one of two hundred teenage girls walking through the Ozark green on a muggy July evening.

What is “sanctuary”? To me, sanctuary is a refuge, a retreat from the noise and myriad voices competing for our attention.

On a sweltering August afternoon when only a man deranged would return to Savannah, I wheel up.

.jpg?ixlib=gatsbyFP&auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=max&q=50&w=3676&h=2879)

How can I explain the joy that I get from reading? Words can't fully express it.

.jpg?ixlib=gatsbyFP&auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=max&q=50&w=3750&h=3750)

Last weekend felt like coming home.

Fire, 20 miles south, 30% contained.

“Who else is on the reservation?” asks the assistant naturalist, who appears to be around the same age as me, as she finds my name on the registration list for a bird talk.

I go there again and again, never tiring of the place. When I’m away, I imagine that it waits for me, no matter how long my return might take.

Sunday, a day early, but those murderous temperatures, and we’d had our gators if not our dolphins, our tidal marsh kayak if not our sunset river cruise, decent meals if never a feast...

I don’t want to worry. But I do. I want to lay my burdens down and find rest. But I don’t. My mind interferes.

I arrived at Nrityagram dance village in Karnataka, India in July of 2014 with the monsoon rain.

Earlier this morning, he called his parents with the bad news. He had just learned he has Covid-19.

Sunset, palm trees, and chicken on the grill - these three ingredients should have made for a perfect evening.

Cherished family memories ground and bond us, enriching our lives in ways nothing else can.

That hot June night, my mother made me ride with her in the dark blue Dodge out to Route 38, what we thought of as “the highway.”

What a dinner Monica has prepared for us. First, she and Allesandro and the younger couple with the baby girl, bowls of snacks and a glass of local red wine in the shade of the towering fig tree.

When I was a girl, I knew only one thing about Loop 360: it was the road that took my family to the barbecue restaurant overlooking Bull Creek

Years before I went to restaurants with dishes like “scallop mousse” and “seaweed gremolata” on the menu, I was a Jersey girl who loved bagels.

I cleaned out the cookware cabinet in my kitchen. Marie Kondoed it.

The gutter overflowed with brown, spiky husks like the aftermath of a tiny urchin apocalypse.

What could she have wanted with all of those empty containers, so meticulously cleaned and stored so haphazardly around the house?

A reflection in ten steps

Last fall, my dad showed me five three-ring binders he kept in his home office. Each was filled with original handwritten letters, many of them yellowed with age and written by my great-grandfather

Cleveland was the place we went back to. Like homing pigeons or salmon returning to spawn. Cleveland felt like no other place, not home exactly, but something separate and apart.

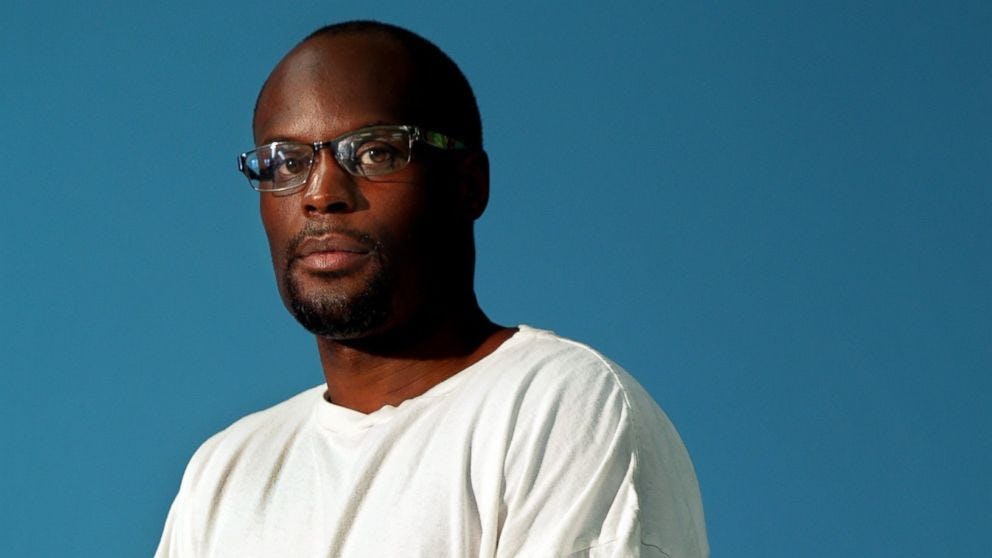

At 18 years old, sitting in my prison cell, I was very lonely. I had just been sentenced to 241 years in prison.

The George Eliot Fellowship greeted my second cousin and myself in Nuneaton with hot tea, biscuits, and a copy of every book that George Eliot had ever written.

All that remains of Gridley’s store is some time-curled paper copies of these supposed facts recorded by someone associated with the State of Connecticut Historical Commission for the Historic Resources Inventory and haphazardly shoved in a purple file folder marked “House Documents” by me.

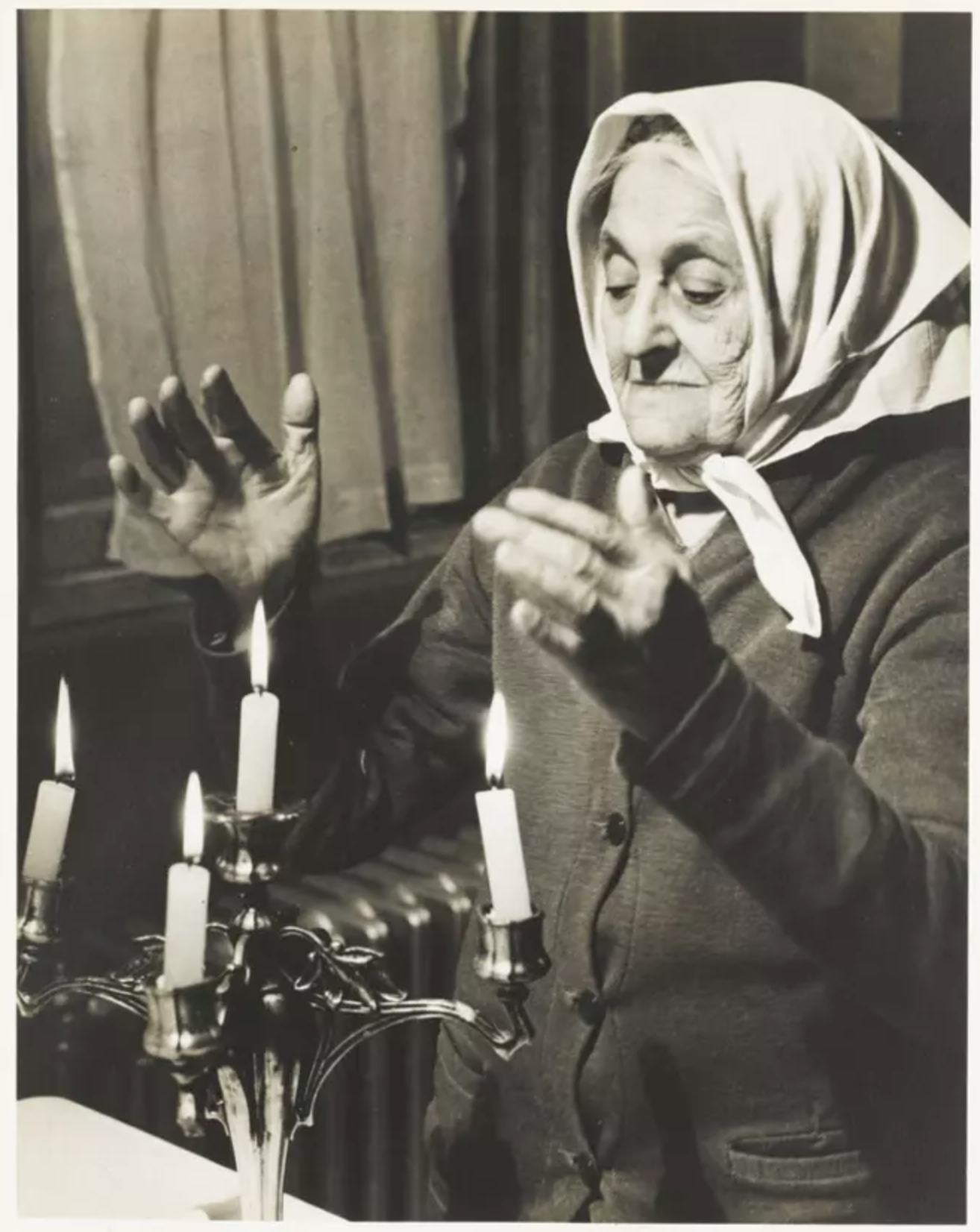

Tape recorder on, I tried interviewing my 75–year old grandmother for a 6th grade school project. “I can’t talk about it,” my Bubbe said in her Russian-English accent.

Once upon a time… all history books should begin like a fairytale.

On day three of 2022, I found myself giving our Christmas tree the stink eye, its presence a reminder of our Covid-stricken holiday season.

In the summer of 1997, at five years old, I place my grubby little fingers on a thin trunk, the grey bark slightly soft beneath my palms. . .

In July of 1998, on a high school auditorium stage in central New Jersey, I played the starring role of Mirabai, a 16th century Hindu bhakti poet and mystic, in a semi-classical Indian dance drama.

I have often felt, throughout my life, that activism was a “given,” meaning that it was something I was expected to do.

Once I was in New York with my partner. The MOMA was closing in 30 minutes, so we decided to pay full price to see Starry Night.

.jpg?ixlib=gatsbyFP&auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=max&q=50&w=5431&h=5665)

When winter rolled around and the other kids were busily cutting paper snowflakes, I was drawing circle snowmen and triangle Christmas trees...

I am a former refugee, and a tea fanatic, living in Ottawa, Canada. When I rented my first house in the city, I understood that my love for African tea would be a trigger for racism.

.jpg?ixlib=gatsbyFP&auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=max&q=50&w=2516&h=1792)

The hot, muggy Maryland summers of my childhood were filled with outdoor activity. Some of this time was spent, willingly or not, helping out in the family garden.

From the beginning of time, people have faced tragedies. Why do some adapt better than others? It's the history of my family that encourages me.

A reflection upon Wendell Berry’s “membership” from a suburban neighborhood...

The gardener is an artist, a creator, and an architect... the serenity in the garden sings to their soul.

As the ocean air spritzes my face on a late morning this past June, its saltiness meets the saltiness of the hot tears rolling underneath my tortoise-rimmed sunglasses.

It really happened: I received the things I was asking for: the simplicity, the sustainability, the radical freedom I desired.

That day at the 90-acre park in the northwest suburbs of Austin, there were signs of life everywhere, and I was one of them.

It was crawling next to Sara for a few seconds before she noticed it . . .

The trees hold earth’s history. The pages revealing the evidence of the planet’s stages through the ages are bound most accurately not between the covers of a textbook but between the core and the bark of the oak, maple, pine, languishing ash.

Worshipping outside for an extended period of time has been an invitation to be surprised by natural elements we cannot control.

Imagine for a moment that our skin was a transparent membrane which revealed the inner workings of the body. That we humans had been designed in a way that left the mechanics and chemistry of our anatomy in plain view

I attend Clark Atlanta University in the West End of Atlanta, an area where 90.5% of the population is Black and the median annual income is around $34,000.

There is a place we return to every summer by the Gulf of Mexico. It has a long winding sandy path we walk on to the beach, covered with old oak trees, reaching to the sky with long branches that hang low and thick over the path like a mother’s hug.

I grew up in the rural suburbs of Kenya, where farming was the primary source of income for most households. My fascination with plants, farming, and the environment stemmed from my mother’s love for gardening.

A whisper of cloud stretched across the sky, as we stepped out of the lodge. We still had a half-hour to wait for the sun to come up, but the cloud already burned orange-mauve, spreading a pale rose glow onto the snow blanketing the meadow.

Early on a summer morning, before the heat held the city captive in its stagnant breath, I sat on a bench in Madison Square Park looking at Ghost Forest, an installation by artist Maya Lin. This barren grove of Great Atlantic white cedar trees stood like weathered sentinels in the verdant park.

Learning to love New Jersey roughly translated into learning how to love myself.

As a photographic practice, fragmentation has always fascinated me. Images of dark corners in brightly lit rooms; photos of isolated limbs curving toward another subject; highlighted facial expressions and gestures in a crowded, chaotic space.

I am listening to Eckhart Tolle on a stale bus filled with 50 Greenwich moms, seated next to a boyfriend I love but do not like, on a dark gray January morning headed to the Women’s March on Washington. It is 2016.

How does one heal from the death of a child? My son, Wells, died of a heroin overdose last year, the weight of grief shaped me into a woman I did not know – angry, bitter, hating the world and God.

When I was 21, I visited the British Museum in London. I toured the winding exhibits that showcased artifacts from around the world with my college roommate in tow.

The school to prison pipeline is not just a theory. It is not something that social scientists conjured up. It is real life.

My grandmother loved flowers. Originally from a farm in South Korea, she knew how to tend to things, how to get them to grow and thrive.

On Sunday, March 21, 2021, my mother began a self-imposed, nine-month period of silence and isolation at her apartment in central New Jersey. Had it not been for Covid-19, this experience would have taken place in an ashram in Rishikesh in Uttarakhand, India, in the foothills of the Himalayas.

About 20 hours after my second COVID-19 vaccination, I awoke from a nap with a foot cramp that took my breath away. I hobbled to the bathroom for more Ibuprofen, then sat down at my desk and reached for the last pen in the box.

I watched from my window as my father-in-law pulled up in front of our house with the trailer hitched to the back of his truck. He got out and lowered the metal ramps at the back of the trailer down to the ground and undid the straps that had held the wrecked car in place on the trailer from Ohio home to Connecticut.

At first, I attributed the feeling of unsteadiness that I felt in college to being far from home; I envied my friends who drove home on weekends to do their laundry. But by the end of my sophomore year, I knew that something was wrong.

May 25, 2020 changed America’s trajectory. On that day, Minneapolis police officer, Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd. This murder sparked protests in cities across America.

Through dreams, it is possible to fly very high; to tell secrets without fear; to meet someone who we don’t see anymore; to perceive that impossible things come true when we fall asleep.

The morning light beckons. To the east, the sun rolls over the ridge, a yellow beacon piercing the gaps in the tall evergreens, blinding and bright.

Sudden grief overwhelmed me to a point where I couldn’t function in my second year of college. I had never viscerally experienced an emotion so deeply it made me sick.

Near the end of our work together, I mentioned to my therapist that I’d been feeling “weirdly okay” lately – for the first time since the betrayal that ended my engagement and propelled me into therapy, I was sleeping better, spiraling less, and even thinking of my ex in a more detached way, when I thought of him at all.

You are not the same shape that you used to be. Your body has grown solid. It’s filled out the peaks and valleys of your ribs and hips, and there’s a slight glow in your cheeks.

I am a former refugee, and I held a factory-floor job in Canada in 2018 on arrival. I woke up at 5:00 am for a supposedly eight-hour job that extended into 12 hours when you counted the time it took me to climb endless stairs and the necessary three-hour Metro train ride to get there.

What happens when you’re past the point of talking about it? What happens when I’m abundantly aware of my mental health to the extent that I’d much rather just step away and ignore that nagging itch in my head?

A tall Victorian at the end of the line for the J-Church streetcar was home to The Integral Counseling Center. I caught the streetcar a block from my apartment on that most rare of things in San Francisco, flat ground, and rode the car as it lurched around the curves up a very steep grade.

My friends know me as ‘Jen’, but marketing agencies know me as ‘a mid-20s American woman.’ I am the target demographic for those shilling self-care products, and I am bombarded with ads for them constantly.

There is no magic deeper than re-telling a story, for you are giving yourself agency to assign meaning and (most importantly) to assign usefulness to time and events. When fairytale writer Hans Christian Andersen wrote, “Our lives are fairytales written by God’s fingers,” it was not just a cute ditty— it was a magic healing spell.

“You healed yourself through writing.” a friend said to me, her eyes locked to mine through the Zoom screen, as I finished telling her my story of how I became a writer.

I stand alone by the lakeside, music spilling out of my headphones into my ears and out across the water, the notes rolling through the air like wisps of smoke dancing from the tip of a newly extinguished matchstick.

A few years ago, I travelled to Sydney, Australia where I particularly enjoyed going on scenic Australian bush walks.

Late one night in 2011 I attended a reading by W. S. Merwin...I was a senior in high school and, though I had only known he existed for one week, already zealous about his genius.

Pregnancy should not have taken me by surprise. As the daughter of a nurse, and the granddaughter of three doctors – one of whom set up a reproductive health clinic in the 1960s – I was well versed on everything from anatomy to childbirth.

To say that the pandemic slowed life is uncontroversial. Across the world, many people ceased travelling, commuting, and disposing of their leisure time freely.

Who do you want to be? And what does “being in community” entail for you?

The Covid-19 pandemic has made it clear just how much we depend on one another. We count on those around us to take the public health precautions that will curb the spread of the virus; on essential workers to care for our health, to provide us with food, to keep public spaces clean.

The familiar bell pierces the dewy March air and everyone rushes into the gymnasium, sneakers and sweatbands at the ready. I pull my thick hair up into a ponytail, wincing as I touch the burn on my left ear, another casualty from my daily standing appointment with my straightener.

When I run into Ron, we speak from a distance, both masked, over six feet apart. Today, the greater the distance from new people, the safer I feel.

I’m a Taiwanese American Episcopal priest who is on her third career and living in her eighth state. Trying to describe “my community” can get complex and messy.

Hold my hand, dear reader, and accompany me to the realm of childhood— that place that is both real and imagined.

Because I had not attended regular church services during my childhood, I had previously viewed communal worship as nonessential to living the Christian life. I envisioned it as helpful to some, but not a requirement of Christianity, a personal relationship with God, however, was.

I was a tanned and bright-eyed college freshman at an evangelical university in Southern California when I first heard the phrase “building community.”

After moving out of my parents’ house, I stopped going to Mass every week. But whenever I found myself struggling, I’d always find my way back to the Catholic Church.

“What do you think people see you as when you walk on the street?” my mom asked me rhetorically on the phone a few weeks ago. “They see a Chinese person. And people here can be so discriminating,”.

On my morning walk to St. Giles Cathedral I spotted a performer who posed daily as a magically levitating “Yoda”. You know, from Star Wars.

When I was younger, the concept of “faith” didn’t make much sense to me. I grew up in Australia, where religion is not part of public life or much spoken about. My parents were raised Anglican, but when the topic of religion came up they would say things like “I wouldn’t get involved in that..."

Have you found yourself working remotely since last March? Maybe you are happily working from home and don’t miss being in an office. Or maybe your current “office-mates” involve young children and/or pets who don’t always follow the boundaries of work-life and home-life.

When I was a child, I would frequently sit on the edge of my bed, looking through my small window, out at the moon. At the time, my goal was to become an astronaut.

Standing in line at the Rock Café, I am jolted by the realization that I can no longer see like I used to. In classes, I begin to test myself by sitting in row 6, 7, 8, watching for when the professor’s facial expressions become harder to read.

With so many Advent Devotionals available today, how can you decide which one is right for you?

For many Christians, myself included, the Covid-19 pandemic has substantially interrupted the practice of our faith. Because of coronavirus restrictions, I have not been able to attend Mass in person since March. Though I appreciate the considerable efforts of parishes to offer virtual liturgies, tuning into Mass from my kitchen table while I eat a bowl of cereal just isn’t the same.

I find the term purity culture somewhat ironic. The persistent focus on sexual restraint limits the depth of our understanding of what purity is.

I was five years old when I first became a Christian. I say first because I would go on to try praying the same prayer countless more times, never sure if I’d done it right.

I have been visualizing what it might be like to collect water from a stream by trying to grasp it. My fists are clenched and my grip is tight as the cold sensation slips through my fingers over and over again.

When I was seventeen, I wrote a one-man play called “Gates and Chains,” dramatizing the Christian journey of faith. The protagonist, a version of myself, ultimately fails to progress in her spiritual journey because she refuses to release the delicate chain on her wrist. The chain of “familiarity” is comfortable, so she keeps it.

Complementary colors are in fact direct opposites: red to green, orange to blue. Along the same line of logic, every emotion heightens its opposite. True presence begets the most soul-aching absence and vice versa. There is nothing like a pandemic to hit this lesson home.