Five years or so after the Civil War ended, Edwin Gridley opened a store in what would one day be my house. He catered mainly to the guys who worked in the knife shop across the street. All that remains of Gridley’s store is some time-curled paper copies of these supposed facts recorded by someone associated with the State of Connecticut Historical Commission for the Historic Resources Inventory and haphazardly shoved in a purple file folder marked “House Documents” by me. All that remains of the knife shop now are the stone foundation by the waterfalls that powered the mill, perhaps a knife head churned up by the earth to be discovered by a fortunate wanderer with a metal detector, and a street sign bearing the name: “Knife Shop Road.”

My village of Northfield, Connecticut is barely more than an ink dot on a map these days. People still come from out of town to hike around the waterfalls, fish the pond, visit the old cemetery, but mostly, it’s a quiet place. As I look out on the falls and the lichen-covered stones, I try to imagine my corner of the world as the bustling place it seems to have been in the 1800s. There were craftsmen making clocks, flutes, spinning wheels. Knife-making experts from Sheffield, England established the Northfield Knife Company here in 1858.

The internationally-known company employed 120 people and made 12,000 knives a year. Their knives were even featured in the 1893 Columbian World’s Exposition in Chicago. In addition to Gridley’s store on the main floor of my current abode, there was also a bar in the basement. In the early 1880s, Frederick Hodson opened Northfield’s first saloon there. I find it amusing to say “first saloon” since now there are none. In fact, our only “establishments” in town are a congregational church, the library, and the volunteer fire department.

As I read the paperwork on my house, I find it interesting and exciting but also irrelevant. What bearing does it have on my own family’s life that a carriage and wagon maker named Merritt Clark built our original house circa 1833? When my father-in-law was nineteen, he built an apartment over the garage for himself and my mother-in-law. After a few years, they built a house a mile from here. In 1994, my husband and I moved into the apartment as newlyweds. In 1998, we had a fire. After that, we worked on the house itself and in 1999, we moved in.

In the process of reconstruction, we uncovered some old wooden beams, probably original to the house. These beams are not smooth. They are dinged up with marks that look like straight fish scales. Perhaps cut with chisels. Where nails or bolts would be, there are round wooden pegs. We retained what we could of these beams. One is visible on the right-hand side of the stairwell. A second beam at the front of the house runs parallel to it and supports the roof/ceiling in our bedroom. We kept the beams to honor the past of this house and to remind us not to take for granted modern technology like hammers, nails, and power tools.

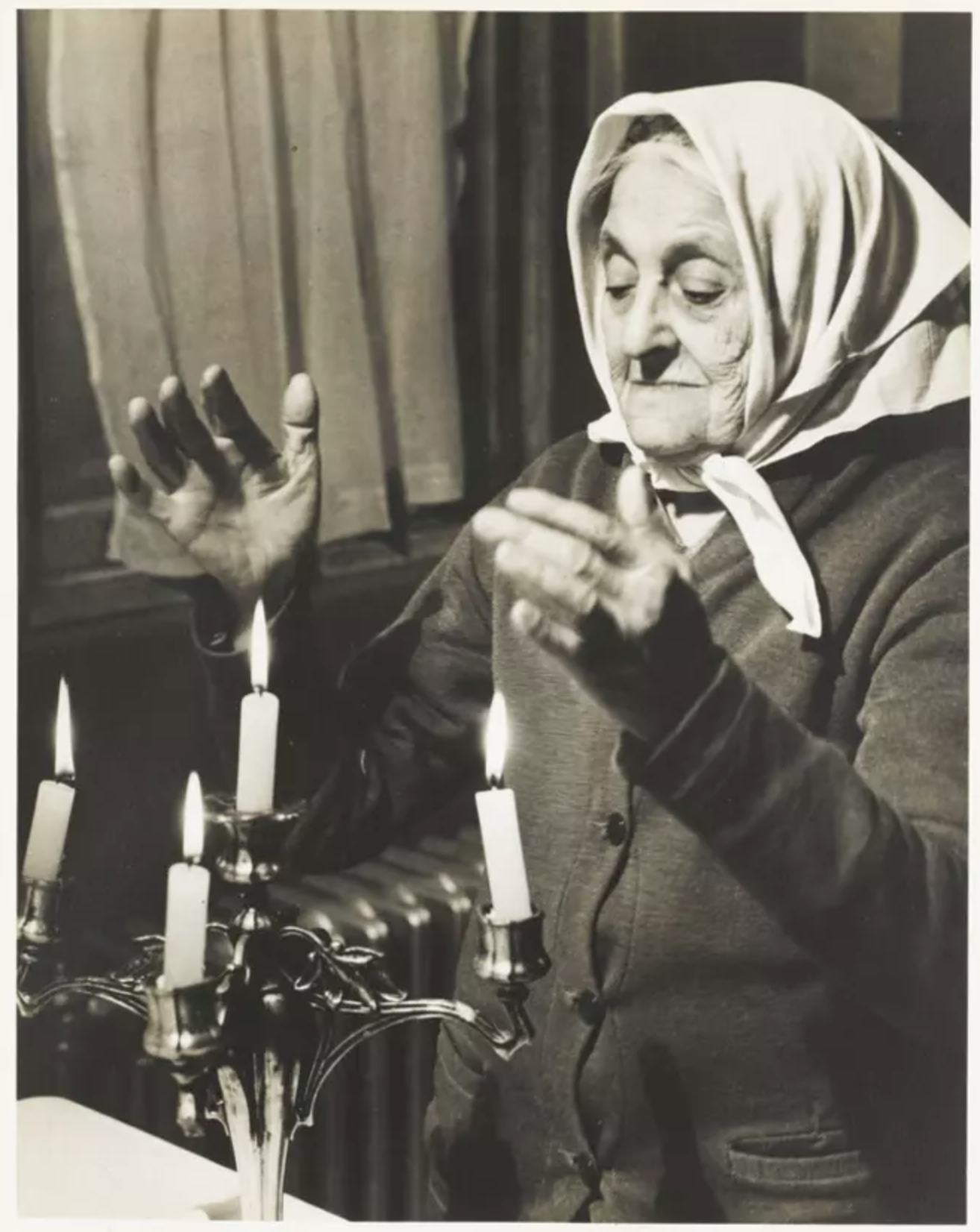

But I have to admit, even though I wake up in the morning with a clear view of the notched wood, most days I don’t even notice it. I rarely take the purple folder out of the “Household” drawer in the file cabinet in my home office to review its contents. What’s an old knife shop compared to the crook of my daughter’s forefinger as she lifts the peanut-buttered English muffin to her lips? There’s more history for me in the crook of that finger than there is in ten file cabinets. That finger curls the same way Grammy’s did when she held the goldenrod-colored plastic fork and whipped the mashed potatoes, holding the Revereware pot at a 45 degree angle, steam still rising.

Grammy would have potatoes at every meal. Sometimes baked, sometimes mashed, sometimes scalloped with ham. This daily spud routine was most likely a carry over from her upbringing in Maine. She lived in the country. Among other things, her family grew their own potatoes. Later on, when she no longer farmed, she would buy a season’s worth of potatoes from a farmer and keep it in a cool dry place. Although we don’t buy in bulk like that, my mother and I still carry on this domestic tradition, storing dirty potatoes in a single layer in a cardboard box in the basement.

We all seem to find glimpses of the past in different places. When Papa took the steak knife and sliced a grid pattern into the halved baked potato and watched the margarine melt into the valleys, did he think of his childhood in Maine and that time he jumped off the Bangor-Brewer Bridge into the Penobscot River and chipped his tooth? Were potatoes one of his history books the way my daughter’s hand is one of mine?

These things have meaning to me because they are part of my immediate story. The paperwork in the folder, not so much. It’s not that what happens outside me doesn’t affect me in some way. I am, after all, a part, however small, of the history of the world. Sometimes I just wonder what my part is. How I fit into the grander story. Most likely, unless I write a book about my life, no one else will. And would it really matter anyway? The greatest impact most of us can have is on those closest to us.

I wonder where my story will show up. On curled pages in my kids’ file cabinet? In the “cloud?” Maybe it’ll show up in my daughter’s handwriting. Maybe she’ll pause, stunned, as I did the day I wrote a cursive capital H and discovered I had formed it the same way Grammy always did when she signed her Christmas cards.

As much as our parents’ past is recorded in our genes, our future is written there as well. Each day, in fact, we act off of this living blueprint. How we look, how we act, how we eat depend, in part at least, on our genetic code. While we are reading the code, we are also simultaneously writing new bits for future generations. Adding to our living historical inventory.

There is so much more to our stories than type-written words on a page. I return to the brittle paper in the folder. I learn the names of a few people who trod this same patch of earth I call home. I learn the approximate time they were here. I learn their occupations. I can place them on the timeline of this town, this state, this country and try to extrapolate why and how they did what they did when they did it. But this doesn’t tell me who they truly were. How they took their coffee, the gossip they overheard while they poured drinks and stocked shelves, how they spent their Sunday afternoons.

We don’t know where our stories will turn up in the future. If at all. We have no guarantee of how what we do today will affect generations to come. We can only hope to do the best we can with what we have. And continue to tell our stories.

Attempting to insert myself into the historical inventory of my house, I realize I, too, have a unique place in its history. An updated version of Box 19: The Historical or Architectural Importance of my house might read something like this:

In the 1870s, Edwin Gridley kept a store in this building, and in the early 1880s, Frederick Hodson kept a saloon. Both served employees of the Northfield Knife Company which, at that time, was located across the road. After the knife company relocated, the store closed and community pressure caused Hodson to close his saloon. The building was converted to a private residence. George and Josephine Nicholson obtained ownership of the property in 1936.

In the 2020s, a home was kept by DJ Nicholson (George and Josie’s great-grandson) and his wife Amy Nicholson. In the kitchen which formerly served as Gridley’s store, they offered comforting meals including lots of potatoes, crockpot meatballs, and a legendary chocolate cake. In the basement which was once Hodson’s saloon, they housed a wood furnace which kept the home fires burning through the long New England winter nights. They catered chiefly to their three children who lived with them but also served surrounding communities by working as school teachers most of their lives.

My story of my time here will come to an end and someone else’s will begin. All of our stories are unique, timely, and part of the grander history of this place.

Amy Nicholson finds grace in ordinary places. She writes by a waterfall in northwest Connecticut where she lives with her husband and their three amazing kids, an aloof cat (aren’t they all?), and a black lab who doesn’t know she’s not a human. She has been published in Country Woman, Green Mountain Trading Post, Today’s American Catholic, among other places, and on her website.

Discover more from Amy Nicholson .