The George Eliot Fellowship greeted my second cousin and myself in Nuneaton with hot tea, biscuits, and a copy of every book that George Eliot had ever written, anniversary editions which the Fellowship had also edited and introduced. My cousin had found the Fellowship online, and two of its members were delighted to give us a tour of the Northern Warwickshire area. There George Eliot had spent her youth, preserved in Scenes of Clerical Life, The Mill on the Floss, and (arguably) Middlemarch. These books, the tour, the Fellowship’s rehearsal later that evening of a two-act adaptation of Daniel Deronda – all came free. The only price? Our sincere interest in George Eliot.

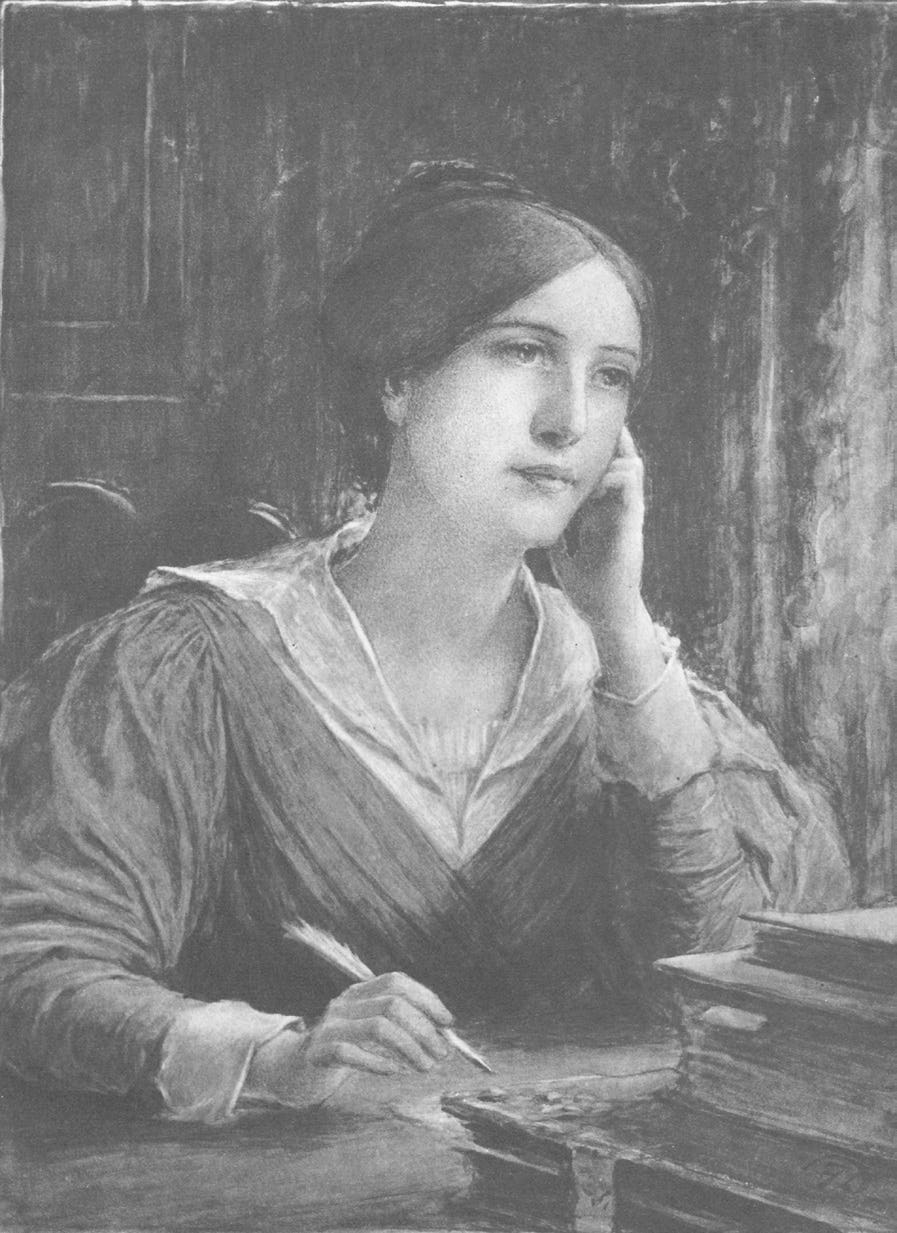

I felt like a fraud. It was mid-July, the summer of 2016. In March I had received a grant from my university to travel to the homes of female authors. My plan was to investigate the setting, natural and domestic, in which these women had written the novels that had influenced my own writing. Yet I had never read George Eliot. I had intended to read Middlemarch in high school; then junior year of college; surely at least two weeks before I arrived in England; hopefully by the end of the drive to Nuneaton… I stumbled into the Fellowship’s visitor center having just finished Middlemarch, only to be greeted by George Eliot’s biggest fans.

After meeting the Fellowship, my cousin and I drove to our hotel: a Premier Inn abutting Griff House, where George Eliot lived as a girl. The majority of Griff House had been transformed into a Beefeater, the British equivalent of a Bob Evans. After a dinner of boiled vegetables and fried fish, the manager took me to a section of Griff House yet unconverted. A small vestibule behind a door long disused, it had become a storage area for chairs and cardboard boxes. The manager pointed to a leak in the ceiling, beneath which a bucket collected water. “She walked here, but they haven’t kept it up.”

For all its enthusiasm, the Fellowship fights an uphill battle against time and its handmaiden: our apathy. The joy of the world is in the living. It’s in your children, your local park, a frothy beer in a cozy pub. Eliot would agree. Her novels concern her present, and they concern it so vividly that they are engrossing even today. People who choose to spend their life resurrecting the past seem strange, even morbid. In college, I majored in history, and most people I met outside of academia asked me, “But…why?” Such conversations went, “So you want to be a historian?” “No.” “A teacher?” “No.” “…Unemployed?”

If studying history has taught me anything, it is that masses of people are frequently wrong, all at the same time. Knowing this doesn’t make it any easier to confront the same opinion over and over. As a history major, I often wondered, ‘Why am I doing this? What is this good for?’ Yet I loved what I studied, from English constitutional law to Chinese intellectual history. Not once did I wish to change my major, though more than once I wondered whether majoring in history was my symbolic rejection of dominant cultural values, such as having a clear path to a well-paying job.

A confession: I am now studying medicine. When I made this change, I had a hard time telling my former professors. I felt ashamed, as if I were conceding society’s point. If history were so important, I wouldn’t study anything else, right? Interestingly, since my transition, I have rarely been asked to justify my interest in science. In fact, people demonstrate a deep incuriosity toward why I study medicine, as if the reasons are so obvious. Perhaps they are. It’s nice, I must admit, not having my life choices challenged by strangers I meet in Central Park. Yet in some ways I miss telling people I study history. I miss forcing myself to answer the question, “But why?”

Before college, I lived for one year in China. Toward the end of my stay, I traveled to Tongren, a small town in the northwest inhabited by Tibetan monks and Muslim Chinese. When I visited, the only new construction was a towering black police headquarters, its glossy exterior in stark contrast to the surrounding dilapidated buildings. At the furthest edge of town stood a monastery. In front was a signpost indicating that it had burned in the 1980s, then been rebuilt. I remember asking our tour leader why. He stared at me and said, as if the answer were obvious, “The Cultural Revolution.”

The Chinese Cultural Revolution began in the mid-1960s and lasted a decade. Mao, his power in the Communist Party waning, condemned “Capitalist roaders” steering China back toward its feudal past. Students rose to defend Mao’s ideals, pilgrimaging to Beijing to become Red Guards and revive the revolution. Cities were overtaken and burned by factions of Red Guards. In public ‘struggle sessions,’ ordinary individuals and famous intellectuals alike were humiliated, tortured, sometimes killed. The enemies of the revolution were the stewards of China’s past: its artists, its scientists, its historians.

In medicine, if you wish to learn the purpose of a molecule, you remove its gene in a mouse. Then you see what pathology results. Living in China, I felt as if the Cultural Revolution had knocked out the molecule for history. This experiment created a haunting absence, not just in the buildings lost, but in the people I met, their years of loneliness and lost potential: pianists with mutilated fingers, physicists who spent their best years in rural isolation. Despite its bloodshed, the Cultural Revolution failed to achieve its goal. Today, China teaches its past as a period of glory, rather than shame.

As a history major, I often felt jealous of China’s reckoning with its past. The Cultural Revolution had pushed society to admit an uncomfortable fact. History is relevant. It is the spirit, and we the living are the body. Our actions, our beliefs, are not wholly our own. Factory owners use assembly lines to produce goods; flutists read music scored with a system of notes; the local movie theater plays yet another adaptation of Macbeth. These practices feel effortless, even ordinary, but they are products of historical developments. As in mouse genetics, the best way to learn their value is to lose them.

A few months after I returned to the States, my supervisor from China won a grant from the U.S. State Department to visit New York. I met up with her, along with the few other grant-winners, at Battery Park. They were supervised by a chaperone from the Communist Party. On our boat ride from Ellis Island, I stood on deck and spoke with this Party minder. She was an elegant middle-aged woman. I liked her. When she asked what I intended to study in college, I told her I was thinking of history. She nodded and looked up at the Statue of Liberty. “History is a very important subject,” she said.

Two summers after living in China, I interned at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. The Orsay displays art, both French and non, from the 1840s to 1920s. The French call their cultural artifacts ‘le patrimoine.’ Patrimoine means “heritage.” A better translation might be something like, “the soul of the French people, embodied in a collection of objects so valuable they must be owned, or supported, by the state.” Unlike American cultural institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum in New York, which can buy and sell paintings on the marketplace, the Orsay cannot sell patrimoine once acquired.

The Orsay, its clock gazing out over the city like a giant eye, sits opposite the Louvre on the left bank of the Seine. The building is a former train station, completed for the World’s Fair in 1900. By the 1950s, it was outmoded and considered an architectural eyesore. After multiple attempts to demolish it, the Mayor of Paris announced in 1970 a competition to convert the station into a museum. The winning architect, Gae Aulenti, preserved most of the internal structure of the Gare d’Orsay. The broad arcade into which trains once pulled now houses sculptures by Rodin and Carpeaux. Aulenti’s conservative attitude toward the building created one of the most iconic art museums in the world.

Living in Paris, I rarely thought beyond the Jazz Age. Each day I photocopied articles concerning the same narrow window of years. On the Rue des Cinémas by the Sorbonne, theaters played Nouvelle Vague. In the Caveau de la Huchette by the Seine, people danced swing. Watching Ratatouille outside the Hôtel de Ville, a Renaissance creation, I learned that the Hôtel had burned in 1871, then been rebuilt to look exactly the same. Notre-Dame is undergoing a similar restoration following its 2019 fire. Drinking rose on the Rue St Germain, I began to feel oppressed by the weight of history. In Paris, what more is there to do? This is, I believe, what the French call ‘ennui.’

French passion for preservation has guarded France from the predations of globalism, for which I am grateful. Paris is not heading into that grim, homogenous twilight inhabited by Marriotts and McDonalds. However, outside every famous French landmark stand immigrants from Senegal and the Côte d’Ivoire, hawking cheap goods. They speak French because French pride maintained not just French buildings but, for many decades, a French empire abroad. Knowing this dark history can, on a bad day, make all artifacts of Paris’ past seem sinister, speaking the language not of beauty and excellence, but of cultural hubris and conquest.

Working at the Orsay, I was surprised to learn that this paradigmatic Paris was created only recently. Beginning in 1853, Georges-Eugène Haussmann leveled the narrow streets of medieval Paris to make its now-famous promenades and blue-roofed apartments. This Paris, so fanatically preserved, is but one iteration of an ancient city, which has had many forms. One day a more beautiful Paris may be built in its place, but only if the French lose some of their precious patrimoine. After a summer in Paris, I was relieved to return to America. Our attitude toward history may be dismissive, but at least it’s not worth embalming ourselves.

Once I explained to a skeptical New York cab driver my love for history by detailing these differences I see between France and China. For a few moments he was quiet. Then he said, “That’s interesting. Can’t you just read a book about it?” My answer is no, a book is insufficient. You need to spend a lot of time, a lot of time, reading many books, analyzing them, reconsidering your analysis, to begin to put together something so vast as the history of a single person, let alone an idea, a country, a continent, the world. My answer to him in the moment was instead, “Ha ha ha. Reading a book helps.”

Contrast this with what happens when I tell a cabbie I study medicine. His response is usually, “Wow, you must be smart. Maybe one day you’ll replace my heart, huh?” In some ways, the disparate reactions disappoint me. But such responses are also telling. Everybody studies history in school, while nobody studies medicine until the graduate level. This mystery makes medicine seem tougher, though I don’t think it is. Medicine is also acutely relevant to everybody. All of us know what it is like to be sick. History, on the other hand, is like the air we breathe. It is ubiquitous, but we don’t easily see how it applies to us. And, as with the air we breathe, we undervalue its importance.

Over the past three years, the most important aspect of medicine has been a form of history: immunologic memory. During a disease, our immune system recruits T and B cells to fight a pathogenic invader. Once we recover, these cells are deleted, except for a few ‘memory B cells.’ These memory cells function in our body as a circulating archive, reactivated when the same pathogen is encountered again. On this principle vaccines are based. When we cannot make immunologic memory, we are immune-compromised. Accumulating too much immune memory is its own devastating syndrome.

This debate over what to keep and what to discard is a constant negotiation made by our body to live healthfully in the world. It is also a negotiation made by our society to exist healthfully in the present. Throwing everything away is destructive; throwing nothing away is oppressive. A balance must be struck. Rarely are historians called upon to answer such questions. Because history is ubiquitous, all of us are implicated in how we respond. The George Eliot Fellowship is made up of ordinary people. Yet they determine how Nuneaton will balance its Griff Houses with its Beefeaters. The character of Northern Warwickshire, Britain, and the world rests on such decisions.

The last stop on our tour of Nuneaton, the Fellowship took us to All Saints Church in Chilvers Coton, where Eliot set Scenes of Clerical Life. Our guide stood at the pulpit as we squeezed into the nave. Listening to Eliot’s opening to “The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton,” I saw what she described, because I was sitting in it:

Pass through the baize doors and you will see the nave filled with well-shaped benches, understood to be free seats; while in certain eligible corners, less directly under the fire of the clergyman’s eye, there are pews reserved for the… gentility. Ample galleries are supported on iron pillars, and in one of them stands the crowning glory… namely, an organ, not very much out of repair.

Eliot is dead more than one hundred years. Yet listening to her words, I heard a heart beat out of the past. For all history’s practical uses, I would be remiss if I did not mention that, in its study, I have experienced a miracle: human connection, across space, through time.

Claire Ashmead-Meers is from Cleveland, Ohio. She graduated from Princeton in 2017 with a Bachelor's degree in History, Creative Writing, and Chinese Language, and in 2018 obtained a Master's in Fiction from the University of Edinburgh. She lives in Ann Arbor where she studies medicine at the University of Michigan. Her guiding spiritual principles come from Protestant Christianity, Zen Buddhism, and writers like Dostoyevsky and George Saunders.

Discover more from Claire Ashmead-Meers.