The school to prison pipeline is not just a theory. It is not something that social scientists conjured up. It is real life. I write these words from my prison cell in the pipeline to let you know the truth of this experience. What is the school-to-prison pipeline? Is it as simple as it sounds? Are kids pushed from school through a pipeline straight to prison? Well I don’t want to make it sound so cruel but it can happen that way. How does this happen? I don’t want to place the blame on society or the government for the mistakes that young teenagers make by committing crimes that eventually land them in an adult prison.

The school-to-prison-pipeline is a combination of factors. It starts in the communities where inadequate schools are built. Many of these schools are segregated. These schools are often underfunded, overcrowded and deteriorating. Such conditions heighten their chances of being incarcerated in adulthood. Many of the males in these communities are unemployed. Such strains on relationships lead to divorce. Therefore single mothers are left to raise kids on their own. Without the proper male influence many young black turn to neighborhood criminals to be their mentors. These are situational factors that can entice them into crime. The main factors can include peers, thrills, excitement, experience, learning, and economic opportunity. Their community cohesiveness becomes destabilized. All they see is media advertisements that link success to having the best material possessions. However they lack the means and resources to obtain these material possessions. Not wanting to be powerless these youth turn to crime to obtain these material possessions. When they start committing crimes they often drop out of school. When they are caught for these crimes in their mid teens they get certified and are tried as adults in criminal court. They then face harsh prison sentences for their crimes. Let’s remember that some of these teenagers were still in school when they committed the crimes that lead them to prison. Rather, these kids were still enrolled in school or dropped out of school a year or two prior to committing their crimes. They go straight from school to prison.

Troubled teenagers tend to seek out other troubled teenagers and this causes them to get into even more trouble, when they get together for the inappropriate purpose of engaging in more troublesome antisocial behavior. For teenage girls who engage in these behaviors it can lead to promiscuous activities which lead to them having kids. With their lack of parental skills they can end up raising troubled delinquents themselves, thereby perpetuating the cycle. Schools play a prominent part in the school-to-prison-pipeline. Many high schools in poverty stricken ghettos have a high school completion rate of 40 percent. There have been around 1,800 of these schools documented in America. These schools make up half of all the high school dropouts in this country every year. Thus they have been labeled as "dropout factories." Some of these kids suffer developmental abilities which were ignored or they were written off as lazy. Their low cognitive skills combined with the disdain they felt was shown to them caused them to be disinterested in school. When you combine this with kids who did not go back to school after suspension, expulsion, or pregnancy the “dropout effect” is significantly increased. Exacerbating this problem is the unfair disciplinary infractions given to African American children versus their peers. Such unfair treatment causes these students to rebel. When they rebel and drop out of school it leads to them engaging in more delinquent activities which eventually leads to them committing crime. When they are caught they end up in jail and eventually go to prison. Marginalized adolescents rebel against a society that they feel limits their opportunities and don’t understand them. Antisocial behavior makes them feel in control of their own lives. These youth start selling drugs or stealing to buy stylish outfits. Crime also increases their self-esteem. A lot of these wayward youth have been diagnosed with ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder). Children with ADHD are more prone to antisocial activity and drug use. Furthermore they are more likely to be arrested for crimes.

Peer pressure has been adequately documented as the major factor that contributes to youth crime. Peers learn from and share more with their youth peers than they learn from and share experiences with adults. This has become the norm rather than the exception. Let’s look at the root cause of the school-to-prison-pipeline. Statistics do shape much of this problem. Nearly 22 percent of youth in America live below the poverty line. Another 22 percent are considered poor. A child being poor does not happen by chance or coincidence. Their parent’s education, employment, and other factors play into this “culture of poverty”. This can be especially harsh on younger children. I am not someone who just went to school for this and speaks about these things from a theoretical point of view. I lived through these experiences my entire childhood and I vividly chronicle this in detail in my memoir “Humbled To The Dust: Still I Rise." Kids who grow up in low income homes are less likely to complete school or do well in school than their more affluent middle-class peers. Studies have shown that such a lack of educational success can be linked to crime. The crime rate in these communities can be significantly reduced by lowering levels of poverty, better educational resources, and better employment opportunities. Many of the adolescents that travel the school-to-prison-pipeline undergo what criminologists term as the “Strain Theory” which is defined as seeing crime as a function of the conflict between people’s goals and the means available to them. The Strain is the emotional turmoil and conflict caused when people believe they cannot achieve their desires and goals through legitimate means adolescents that live in poverty feel Strain because they lack adequate educational resources. A lot of the young girls drop out of school and have kids at an early age. People who live in such communities suffer from what criminologists call the “Poverty Concentration Effect”. This happens in the most disorganized urban neighborhoods. Many of the kids that are shuttered along the school-to-prison-pipeline live in the American “culture of poverty." The culture of poverty has been defined as “the view that people in the lower class of society form a separate culture with its own values and norms that are in conflict with conventional society; the culture of poverty is self-maintaining and ongoing. Desperate life circumstances prevent them from developing the necessary skills-set, behavior, and lifestyles that lead to educational advancement.

Sadly, I too am one of these statistics. (However, I take full responsibility for my crimes and I do not directly blame anyone or anything for my actions). I have traveled the school-to-prison-pipeline. Now that we have identified the cause we must find a solution. This crisis is urgent. In my future writings and via my future nonprofits as well as through partnerships with schools I will lend my expertise in every way that I can to help dismantle the school-to-prison-pipeline

A Postscript, Education Is a Ladder to Freedom

My journey to educate myself in prison began when I came to prison at 16 years old. I have been in prison over 25 years now and healing continues. Nelson Mandela once said that “education is the most powerful tool that can be used to change the world”. I agree. I also know that education is the most powerful tool that can be used to change a prisoner. Education helped me to thoroughly rehabilitate myself. Before my incarceration my education was limited to street economics and gang arithmetic. On the streets I nearly starved myself academically. Thus when I came to prison and my appetite for education was stimulated I purged myself of every educational opportunity that was available to me.

I was hungry for education so therefore my mind ate books constantly. The more that I learned the more that my eyes were opened to the larger world outside of my street corner. Education arose in me a dedicated desire to contribute something meaningful to the world. When my own personal world became dark, education sparked a light in me that will never be extinguished. The more that I became educated let me know that I could one day become somebody important.

I wrote in my memoir that “education was the anchor that held me still when the waters of ignorance were waging will all around me”. What I am saying is that the reading of books sat me still while others around me moved in concert with prison madness volatile without guidance. When others gave up, education reminded me that there was still hope. I was a lost 16 year child that was sentenced to die in prison. I had no guidance but education helped me to find myself.

The journey to educate ourselves should never end because we should seek to educate ourselves until we reach the grave. When I first came to prison I only had a formal 8th grade education. Therefore academically I started over by learning the elementary basics of fractions and algebra because I had all but forgotten how to do these things. Then came science, social studies and other areas of academics. A basic grasp of these multiple disciplines allowed me to acquire my G.E.D. in a relatively short period of time.

Education can never just be limited to academics. I also educated myself spiritually as well. I learned about morals and how to apply those morals to become a better man.

Education in multiple disciplines helped me develop on many levels that continue unabated to this day. No words can explain the depth of what my journey of education means. It would take a book to even touch the surface, nevertheless I wanted to share some of this journey with you of how I went from the school to prison pipeline but continued to educate myself. I have obtained my Associates of Science degree from Adams State University. I have 11 classes left (30 college credits) to obtain my Bachelor of Arts in Sociology degree (Emphasis in Criminal Justice). We must never stop educating ourselves. Education is a ladder to freedom.

*

Take Action:

Sign petitions to support clemency for Bobby, here and here. And write to Governor Parson.

Write to Bobby to share your support or your response to this powerful piece.

Watch Bobby’s recent interview with CBS This Morning. Read a few recent articles, here, here, and here.

Purchase Bobby’s books on Amazon or Books-a-Million. Read more of his writing here.

Follow Free Bobby Bostic on Instagram and Twitter for legal updates, news, and calls to action.

*

LaFree, Gary. “The Impact of Racially Inclusive Schooling on Adult Incarceration Among U.S. Cohorts of African Americans and Whites Since 1930.” Criminology 44 (2006): 73-103. Print.

Anderson, Amy. “Unstructured Socializing and Rates of Delinquency.” Criminology 42 (2004): 519-550. Print.

Thomas, Kyle. (2015). “Delinquent peer influence on offending versatility: Can peers promote specialized delinquency?” Criminology. 53. 10.1111/1745-9125.12069.

Morris, Robert. “Young Mothers, Delinquent Children: Assessing Mediating Factors Among American Youth.” Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 10 (2012): 172-189. Print.

America’s Promise Alliance. “Building a Grad Nation: Progress and Challenge in Ending the High School Dropout Epidemic.” November 30, 2010. http://www.americaspromise.org/Our-Work/Grad-Nation/Building-a-Grad-Nation.aspx.

Gasper, Joseph. “Drug Use and Delinquency: Causes of Dropping Out of High School?” (El Paso, TX: LFB Scholarly Publishing, 2012.) Print.

Sweeten, Gary. “Does Dropping Out of School Mean Dropping Into Delinquency”? Criminology 47 (2009): 47-91. Print.

Rocque, M. and Raymond Paternoster. “Understanding the Antecedents of the “School-to-Jail” Link: The Relationship Between Race and School Discipline.” Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology 101 (2011): 633-666.

Brezina, Timothy. “Delinquency Problem-Solving: An Interpretive Framework For Criminological Theory and Research in Crime and Delinquency” 37 (2000): 3-30. Print.

Ferrell, Jeff. “Criminological Verstehen: Inside the Immediacy of Crime.” Justice Quarterly 14 (1997): 3-23. Print.

Lindsay, W.R. “The Impact of Known Criminogenic Factors on Offenders with Intellectual Disability: Previous Findings and New Results on ADHD.” Journal of Applied Research on Intellectual Disabilities 26 (2013):71-80. Print.

McGloin, Jean. “Delinquency Balance and Time Use: A Research Note.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 49 (2012): 109-121. Print.

National Center for Children in Poverty. “Child Poverty, 2015”. http://www.nccp.org/topics/childhood.poverty.html

Brooks-Gunn, Jeanne. “The Effects of Poverty on Children.” Future of Children 7 (1997): 34-39. Print.

National Center for Education Statistics. The Condition of Education 2014 (NCES 2014-083) Status Dropout Rates. http://www.nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp? id=1 6

Ainsworth-Darnell, James and Downey, Douglas. “Assessing the Oppositional Culture Explanation for Racial/Ethnic Differences in School Performances.” American Sociological Review 63 (1998): 536-553. Print.

Crane, Jonathan. “The Epidemic Theory of Ghettos and Neighborhood Effects on Dropping Out and Teenage Childbearing.” American Journal of Sociology 96 (1991): 1226-1259. Print.

DeCoster, Stacy. “Neighborhood Disadvantage, Social Capital, Street Context, and Youth Violence.” Sociological Quarterly (2006): 723-753. Print.

Lewis, Oscar. “The Culture of Poverty.” Scientific American 215 (1966): 19- 25. Print.

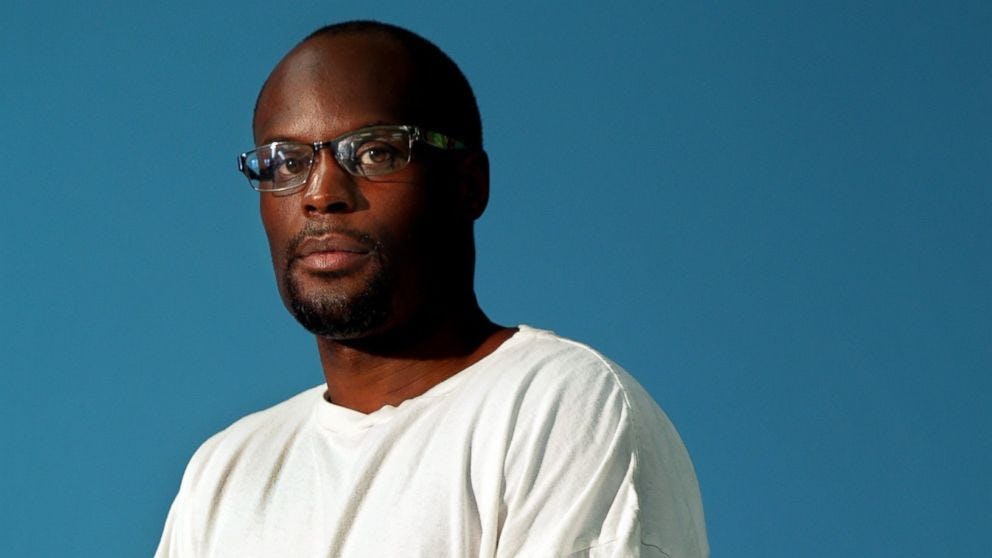

Bobby Bostic was sentenced to 241 years in prison for a robbery he committed in 1995, when he was 16 years old. During his 26 years in prison, he became a prolific writer and college graduate. Bobby's essays showcase his deep style of writing, which Bobby has developed under the very harsh conditions in a maximum security prison. Watch Bobby's recent interview on CBS This Morning and purchase Bobby's books. Bobby was granted parole in 2021 and will be released in November 2022.

Discover more from Bobby Bostic.