On Sunday, March 21, 2021, my mother began a self-imposed, nine-month period of silence and isolation at her apartment in central New Jersey. Had it not been for Covid-19, this experience would have taken place in an ashram in Rishikesh in Uttarakhand, India, in the foothills of the Himalayas. There, she would have stayed in a one-room cottage with two windows, a front window overlooking the Ganges River, or “Ma Ganga” as she called it, and a back window facing a verdant forest. Every day, twice a day, an attendant from the ashram would deliver a silver tiffin of food – a simple dahl, fresh chapatis, a ripe avocado – to her doorstep while she meditated uninterrupted. In prior years, she would video-call us, her three daughters, one by one for the last time in Delhi before withdrawing to this remote place. We held this grainy image of our mother for the designated length of time. The first retreat was forty-five days, the next two were ninety days. And now, nine months, her longest yet.

Only this time, she wasn’t seven thousand miles away. We said good-bye in person the day before she went into isolation – my husband and me, my one-year old daughter and five-year old son, my younger sister, Asha, and her husband. We met my mother in Soho in New York City to see my older sister Suchitra’s art exhibition. Though she and her family lived in Denver, Colorado and couldn’t be with us, Suchitra was there in spirit, in her lush tapestries hanging from the gallery walls. It seemed fitting that our last meeting was in a place of beauty and reverent silence.

Outside on Great Jones Street, on that bright spring day, my mother hugged us one by one, the clan she had created.

“I’m so excited for tomorrow,” she smiled, her expression beatific. Excited to sit in your apartment in the dark? But it was too late for questions. “Don’t worry about anything,” she said. “Let the grace guide you.”

I sighed. The grace, a phrase she referred to often in recent years, was a catchall term for God, universal energy, divine influence, love, fate and truth. I felt a little flare of petulance in my belly. I didn’t want the grace – I wanted my mom. I wondered if my baby daughter would remember her in nine months. I wondered how different we would all be if and when my mother emerged. Every time she went into silence, my sisters and I worried that she wouldn’t come out, and what would we do then?

“Have a great silence, Nani! See you in December!” my son called cheerfully from our Uber before we headed uptown.

Over Zoom, my mother said good-bye to my aunts, uncles and cousins, my screen tiled with their somber brown faces as they listened to her describe what her days would be like. Asha, who lived nearby, would play the part of the ashram attendant, bringing groceries to her doorstep every two weeks. My mother was being guided by Guru Swami Rama, who passed away in 1996, but who was “with her all the time.” As his guidance stipulated, her curtains would be drawn so she could not see anyone, and no one could see her. In that semi-darkness, she would meditate for hours at a time. She spoke of a subtle flow of energy, and becoming one with her true nature. She spoke of light. She spoke of bliss.

“Mom’s Hands” by Charmi Patel-Peña

My mother’s spiritual journey began a few generations back with our ancestors, who were brought from India to Guyana, South America by British colonizers. As indentured laborers on the sugar plantations, they were forced to trade Hindi for English. But family lore has it that my great, great grandfather organized illicit hawans to keep their faith alive. This faith burned bright in my grandfather, who became a spiritual leader as well as a dairy farmer, and in my mother. They were Arya Samaj Hindus who focused on the teachings of the ancient Vedas, or scriptures. I can still remember her teaching me the Gayatri Mantra at our kitchen table when I was just four years old, the Sanskrit syllables strange on my tongue.

For better or worse, that faith, kindled and rekindled from one generation to the next, has dimmed with me and my two sisters. Brought up in Canada and the US, our worldview is much more secular. So far, none of us have been moved to practice any form of religion in our adult lives. But our spirituality plays out in different ways. For Suchitra, it lies in art-making and her studio practice. For Asha, it lies in her work as a health coach. For me, my connection to religion manifested for many years in the form of Indian classical dance, which I began learning at nine years old. In recent years, I have taken refuge in language, exploring life’s many mysteries on the page. All of us have spent time in therapy, processing our emotions and traumas, not through a ritual offering to a sacrificial flame, but through the sharing of our unspeakable truths. None of us knows how to conduct a hawan, how to light the fire in the kund, or which Sanskrit prayers to say when. When my mother passes, this ancient knowledge will go with her.

Growing up in the suburbs of New Jersey, religion was inseparable from the vestiges of Indian culture present in our lives – the Bollywood films we watched in overdubbed VHS, squinting to read the blurry subtitles, our weekly dinners of dahl, potato curry, and roti my mother cooked on her tawa, the saris we wore to family weddings, fumbling over the pleats every time. As a misfit teen, I took these aspects of my cultural inheritance for granted, and was even embarrassed by them. When I visited both Guyana and India as an adult, hoping to reconnect the loose threads of my identity, my experiences as a tourist only highlighted my American upbringing and solidified my place as “other” wherever I went.

But for my mother, India was always home. For her, it was a return to a distant yet familiar place, like reconnecting with an old friend you haven’t seen in years, or in her case, over a century and across generations. Even in New Jersey, my mother was never deterred from reclaiming her Indian heritage, despite the disdain we sometimes received from first generation South Asians. If anything, being Guyanese strengthened her sense of connection; unburdened by ties of caste and country, she was open to all parts of India, from masala dosas and carnatic music of South India, to papri chaat and kathak dance of North India. While the diaspora was busy dividing itself into regionally specific associations, my mother attended every event she could.

At work, in her career as an IT professional, she shelved her Indian identity and became “Sue,” her name shortened to accommodate her American coworkers. But in 2004, eleven years after my parents’ divorce, and twenty years into her career, she was laid off from her last corporate job. “Sue” and her wardrobe of pantsuits and blazers were finally put to rest. My mother reinvented herself as a semi-retired yoga instructor and Reiki master. I think of this time as a kind of untethering. Free from an oppressive marriage, free of the constraints of a nine-to-five, my mother began the journey to becoming herself.

It was beautiful to watch, and also scary. Our one dedicated parent, the stable center of our universe, was finally prioritizing her own needs. Asha was just starting high school when she left for six weeks to complete her yoga teacher training at the Himalayan Institute in Honesdale, Pennsylvania. It was the longest time our mother had ever been away from home. I remember she returned energized, inspired, and more physically flexible than I would ever be.

Soon after, she began following Guru Pattabhiram, a middle-aged yogi with an ashram outside of Bangalore in South India. Initiated by Swami Rama, who founded the Himalayan Institute, Guruji, as she called him, visited the US several times a year to share his teachings, and raise money for the ashram and his school for rural children. My mother was a zealous disciple, organizing events and fundraisers for Guruji’s cause. I can still remember sitting on the floor of a yoga studio in New Brunswick, New Jersey, trying not to giggle as Guruji asked the audience in his thick accent, “Vhereare you running? Vhy are you running?” These rhetorical questions, asked with sober intention, instantly became an inside joke, one that Asha and I still refer to today. Skeptical, and a little snarky, I refused to revere Guruji the way my mother wanted me to. To me, he was a stranger, a bearded Indian man who wore a dhoti and gave my mother a sense of purpose. To her, he was a realized soul connecting her to a lineage of yogis and guiding her on the path to salvation. When he passed away in 2016, I was surprised she was not more upset. “His soul is released,” she said matter-of-factly. I was unfamiliar with this world of great souls who moved between bodies and realms with ease.

For years, she taught yoga at local studios, and later, at her home, in what was once our formal living room. Emptied of its mauve recliner, beige loveseats, and 90s era stereo system, this empty space became the soul of the house. On weekends, she performed Reiki sessions on a portable massage table and taught yoga to a small group of students, including me and my younger sister. On Sunday mornings, we would roll out of bed to find the wooden floor striped with colorful mats, the house echoing with the sound of “Ohm.” My mother wore a new uniform now, her “yoga whites” as she called them – a knee-length white kurta top and white drawstring pajama pants. She led the class in chanting, asanas, or yoga poses, breathing exercises and meditation. At the end, as we lay in savasana, the final resting pose, she placed silk satchels of rice she sewed herself over our eyes, the gentle weight shutting out the world, if only for a few minutes. “So hum,” she chanted. “I am.”

I quickly realized that my mother’s yoga had little to do with the yoga I experienced in New York City, where I eventually moved. These classes were taught in airy loft spaces packed with spandex-clad city-dwellers who brought Type-A dedication to their sun salutations. They were usually led by leggy, limber Americans to a soundtrack of Coldplay or Lauren Hill. My mother’s yoga was far less trendy and much too earnest for the average audience. Over the years, I watched her practice evolve on and off the mat. At a certain point, she was no longer just a yoga instructor; she was an unpaid life coach, therapist, and marriage counselor. Every day, it seemed, someone was sitting at her dining room table, sipping her well-steeped ginger tea, listening to her advice. In time, my mother refused payment for her classes, and eventually stopped teaching altogether to focus on her own practice.

As her daughter, I grew impatient with her spiritual persona, her Yoda-like advice and reminders to focus on my breath. There were times I wanted to shake her. Where is my mother? I wanted to ask this unflappable yogi. But she was right there in her yoga whites, pouring ginger tea.

*

Her first period of silence in 2018 hit me hard. I had become a mother myself by then, and my mom had been a huge support to my new family. For two years, she and I co-parented my son when my husband traveled the world for his work. Though she had given me ample time to prepare for her absence, I missed her much more than I wanted to admit. After speaking to her on the phone literally every day, relaying the minutiae of my son’s existence – Can you believe he pooped twice today? Do you think those size 2 diapers are getting a little tight? – I was alone. But the heart adapts. The journey of her soul was bigger than me.

On her first ninety-day stretch, she wrote to me and my sisters: “…this soul has made a sankalpa or intention 25 lifetimes ago to achieve moksha and am now prepared and ready for that to unfold…” I knew that in Hinduism, there were four stages of life. The first two stages were the student and the householder, which my mother had certainly accomplished. The last two stages focused on detachment from worldly possessions and society at large. If “moksha” referred to the end of the cycle of life and death, did that mean our mother was going to die? My sisters and I panicked, calling and texting each other. Suchitra was ready to book a flight to India and stage an intervention, Asha was unphased, and I didn’t know what to think. I read the email to my husband and a few friends. No one else perceived the message as a death wish and we let it go.

When she returned from that trip in the spring of 2019, I was pregnant with my second child. My mother went back to India later that same year for another ninety-day stretch of isolation, returning a few weeks before I gave birth in December. By then, she had received guidance that she was ready for nine months of silence, a duration echoing the gestation of a human life for the rebirth of a soul. “I’ll give you a year,” she promised, “then I’m going.”

True to her word, my mother stayed among us for a year. She helped me with my baby daughter before Covid hit in March of 2020. We isolated from each other for a few months, before deciding it was safe to join each other’s “pod.” As my mother adapted her plans for 2021, deciding not to make the pilgrimage to India, I was relieved at first, grateful she wouldn’t be so far away in such a strange and unstable time.

But then, the new reality set in. As I went through the mundane rituals of my week, my mother was just forty miles away, immersed in a realm far beyond reality. It was even more surreal than her being in India, and far less romantic than the cottage by the Ganges. After a year of the global pandemic, when people were longing to reconnect, my mother was doing the opposite. The fact that she was being guided by a dead guru began to concern me. I wondered if she had a tumor, like a character on Grey’s Anatomy, listening to voices that no one else could hear. Voices that were telling her to sell her house of thirty years and give away her Toyota Camry. Voices that told her to draw the curtains in her new apartment and not come out until Christmas. Voices that whispered promises of enlightenment.

When I tell people what my mother is doing, the reactions range. The more spiritually minded are always awed, exclaiming at how amazing it is. But others nod slowly, a little shocked. A coworker looked at me seriously, cocking her head, “Is she ok?” she asked. I answered honestly that I didn’t know.

But what I do know is this: my mother has been through a lot. I know that after sixty-nine years on this planet, she deserves a break. Four countries, four cultures. One marriage, three children, fifty years of mothering. Thousands of meals cooked and loads of laundry folded. I cannot speak to the trajectory of her soul, but I can imagine what a relief it must be not to have to speak, explain, console, or defend. I don’t know about moksha, but I can imagine the sheer joy of being undisturbed.

As I write this essay, I am hiding from my two young children in a hotel room seventy blocks from my home. This brief and hard-won sojourn allows me to think clearly, drop into myself and find my voice. Here, I do not have to attend to anyone’s needs but my own. I breathe, I think, I stretch, I write. In this moment, my mother and I sit in parallel universes in semi-darkness, in our quiet caves, shutting out the demands of the world, making time and space to be.

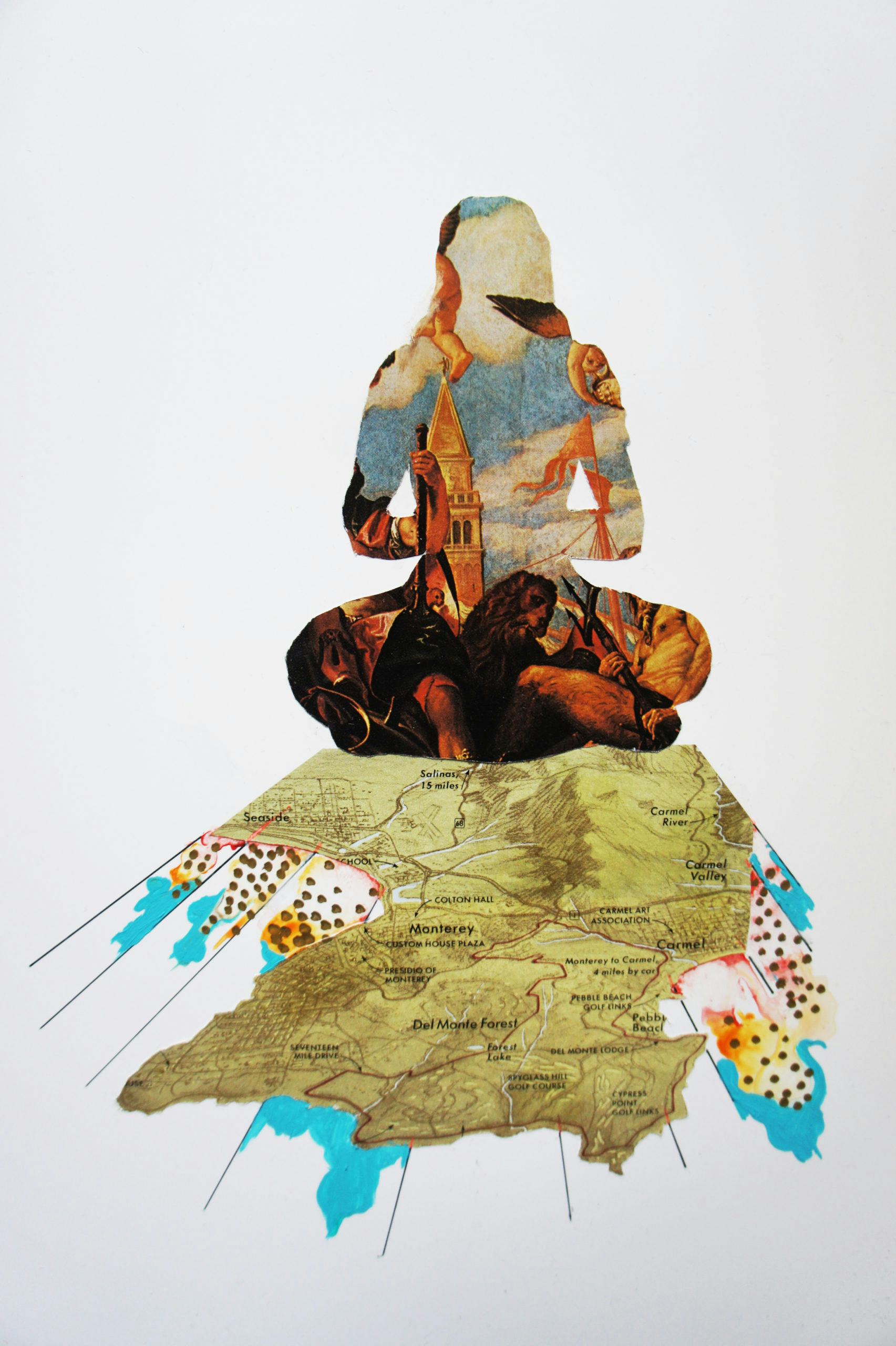

Featured image, “Mirror Image,” by Suchitra Mattai.

Sumitra Mattai is a freelance writer and textile designer. She holds a BFA in textile design from the Rhode Island School of Design and an MFA in Creative Writing from The New School. Sumitra enjoys writing essays about identity, food, design and family. She lives in Harlem, New York City. Follow Sumitra on Instagram, @sumitramattai, and visit her website.

Discover more from Sumitra Mattai.