Body of Work: The Chernikov Family Archive

A chance discovery of an artistic Soviet Ukrainian family’s portfolio prompts curator Myroslava Hartmond to reappraise the importance of life’s small kindnesses.

The bullet that shattered Kurt Cobain’s skull couldn’t silence a million speakers that continue to broadcast his voice, almost 30 years later. The curves of Marilyn Monroe rest in a tiny cemetery in the Westwood neighborhood of LA, but live on in their original glory through still and moving images. The ashes of England’s greatest bards lie in Poets’ Corner, Westminster Abbey, but they are born anew with every reedition of a classic tome, every new theatre production, every silent reading.

Yet perhaps no legacy is as alive as that of the visual artists, whose very hands shaped the clay or bronze, applied the pigment to the canvas, swished a piece of charcoal across the paper – the very same object in the presence of which we stand today. The artwork is the result of contact with its creator’s body. Does that mean that it is an extension of the body, a part of it, a relic? Does it conjure the artist’s presence? Or is an artist’s body of work quite apart from their physical body, a creation all its own, yet bearing an imprint of its maker’s body and soul?

Of all the things that ever slid across my desk, it is the Chernikov family archive that haunts me to this day. A baffling collection of oil sketches, watercolors, drawings, tracings, prep materials for large commissions, as well as family photographs, microslides, and documents – here was my first case as curator. The case remains open, for despite years of hard work, it has amounted to very little on my part. Indeed, this essay – which reads as part research journal, part confessional – may never have been completed if not for the boundless patience of my editor and my nauseating feelings of guilt at failing, once again, to articulate a story that came to me in pictures and fragmented accounts.

Reviewing microslides with family photos and prep materials for larger paintings.

A ghostly encounter posing as a research project, a potential exhibition, a possible venture, a catalogue, it all started with an impulsive purchase on the part of an art collecting relative, whose network of dealers often presented him with bargain finds. With my academic background and professional interest in the art world, I was tasked to do something about it – a Kafkaesque meander that led me down echoing hallways of Soviet buildings to interview surviving friends and relatives, took me on wild goose chases in the archives since reabsorbed by independent Ukraine’s new institutions, and finally to the family plot in Baikove Cemetery, the Ukrainian capital’s celebrity necropolis.

Reader, meet Volodymyr Chernikov, paterfamilias with Brezhnev eyebrows and a steady draughtsman’s hand, Socialist Realist artist par excellence; his loving wife and fellow artist Vera Sogoyan, a delicate and charming Armenian woman, painter of family scenes and flamboyant fruit and flower displays; their troubled artist son Mykola Chernikov, whose neo-Symbolist works never fit the mould imposed by the totalitarian system; and grandson Misha, stage designer, now in his 30s, the only surviving Chernikov, only too happy to exchange the remains of the family’s legacy for foreign currency. ‘There used to be so much more’, he says. I receive his permission to research his family’s history and begin the process of cataloguing and scanning, of interviewing and visiting locations.

Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550) established a vogue for scrutinizing the method and madness of known creatives which persists today. But what of the lives of the not-so-excellent artists who strove, but never made it to the canon, passing away unnoticed and leaving a trail of stained canvas and paper behind? The Chernikovs did well enough in their lifetime – secured state commissions and produced smaller, private works, exhibited regularly and socialized with artist friends, went on holidays and painting trips. They were not particularly different from other Soviet artist families that surrounded them in their niche, and it is this seeming ordinariness that holds a special resonance, a universal truth.

Whenever I revisit the digitized contents of the dusty folders and builders’ bags I took on as my first curatorial enterprise over a decade ago, the world falls away, and out of the corner of my eye I glimpse an ever-present Soviet past. I find myself privy to the intimate dynamics of a living, breathing family, whose joys and sorrows unfold in rooms papered with florals, in blossoming orchards and wheatfields, farmers’ markets, by the sea, on painting excursions to the Caucasus or the Carpathians, around festive tables where glasses clink and lengthy toasts are pronounced, on verandas flooded with summer light filtered through sun-dappled green vines, in the draughty studios of art academies, under the unforgiving dazzle of official chandeliers.

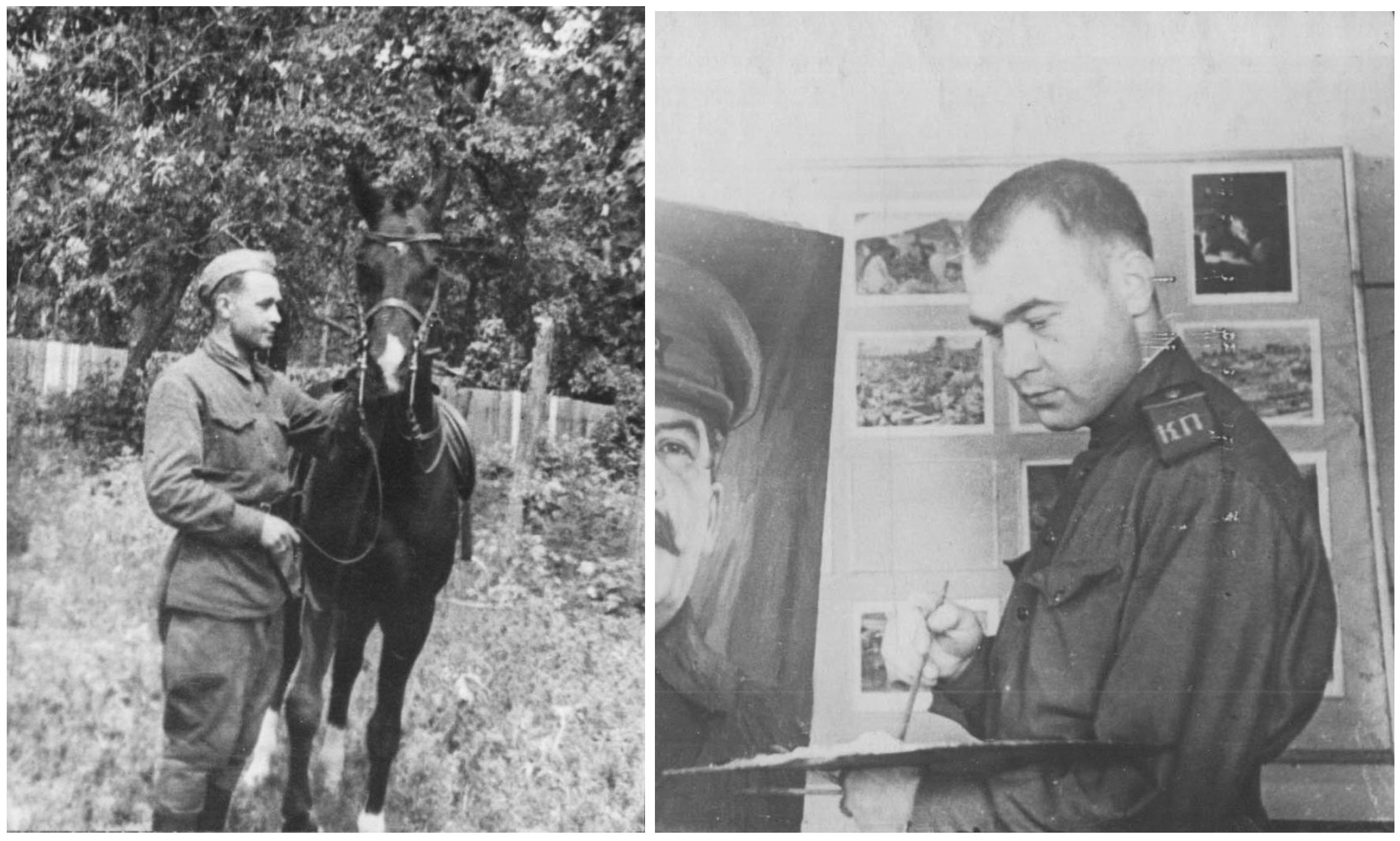

As a minor Soviet cultural official and an Honorable Artist of the USSR, Volodymyr Chernikov had his own car and dacha. His were the drawings of workers and peasants, the carefully executed landscapes, studies for monumental works featuring miners and armed border patrolmen on horseback. A native of Lysychansk, an industrial city in eastern Ukraine, Chernikov’s artistic talent came to the fore when he was a cavalryman during the Second World War. Creating frontline art to boost morale and documenting the war, he was able to practice as a war artist without a formal qualification (a rare loophole in the Stalin era, where an independent artistic practice could land you in the gulag).

Volodymyr Chernikov, war artist (1940s).

Chernikov senior was 27 when the Second World War ended, considerably older than the other hopefuls who came to seek admission to the Kyiv Art Institute – a prestigious institution that counted Kazimir Malevich among its faculty, it attracted artists and architects from across the fifteen Soviet republics, as well as China, Mongolia, and Latin America. Armed with only a small sketchpad and dashing in his uniform, he wowed the admissions committee with his draughtsmanship, and successfully rose through the ranks of the Soviet cultural machine.

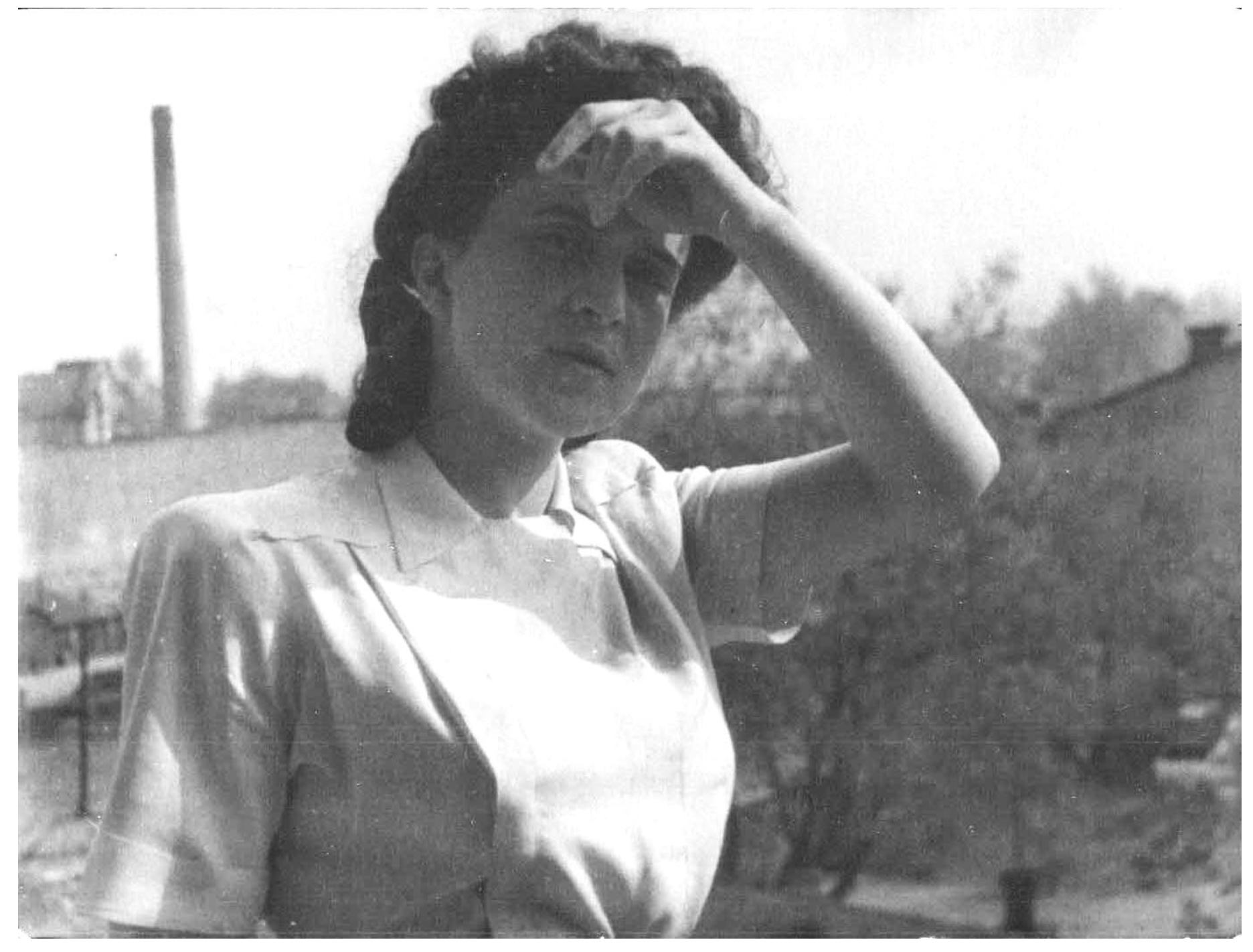

Vera Sogoyan.

It was at the academy that Chernikov met Vera Sogoyan, an Armenian art student, an ethereal, dramatic presence that could have walked out of a Mikhail Vrubel painting. Little is known about her early life, except that she was born in 1925 in Artvin, a Black Sea coastal city in the Caucasus, part of modern Turkey with a majority Armenian population. It is likely that the Sogoyan family moved to the USSR in 1928 to avoid persecution in the wake of the Armenian genocide. Vera’s precocious talent for painting was encouraged by her closely-knit community, and it was said that she arrived at the Kyiv Art Institute with a letter of recommendation by the renowned Martiros Saryan, whose colourful works were recognizable to every Soviet citizen.

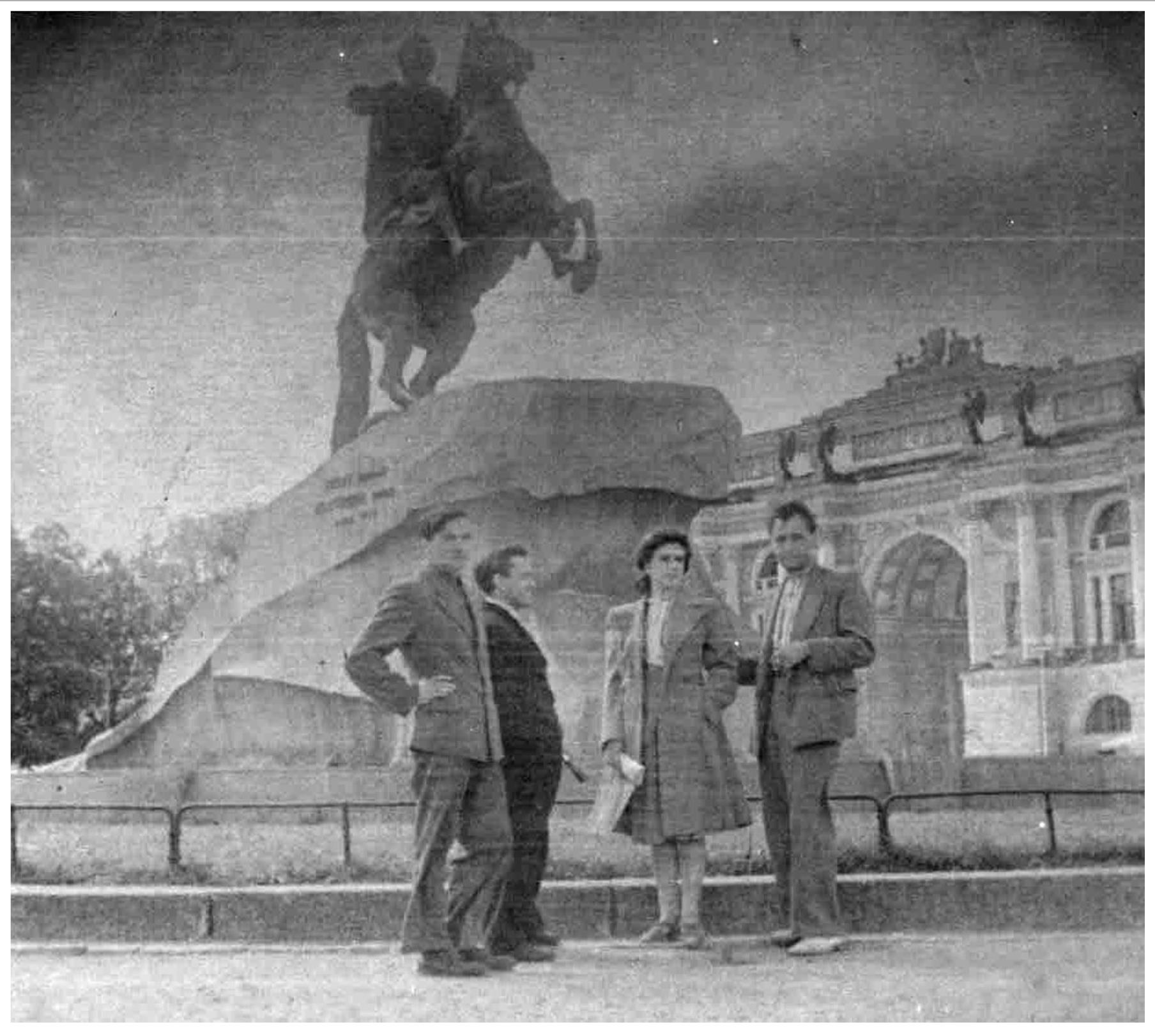

Vera Sogoyan and Volodymyr Chernikov in the 1950s

The young Vera (“Faith”) was a tireless and committed artist, excelling as a student and quick to receive state commissions after her graduation in 1952 – the only legal source of revenue for a Soviet artist alongside official teaching positions, which she also undertook. The indomitable use of bright colour combinations, which is so often associated with Armenian artists, was one of her talents, which she used to gracefully portray a Ukrainian reality in her vivacious canvases of chubby-cheeked infants and happy families.

Vera Sogoyan, ‘Homeward’ (1967)

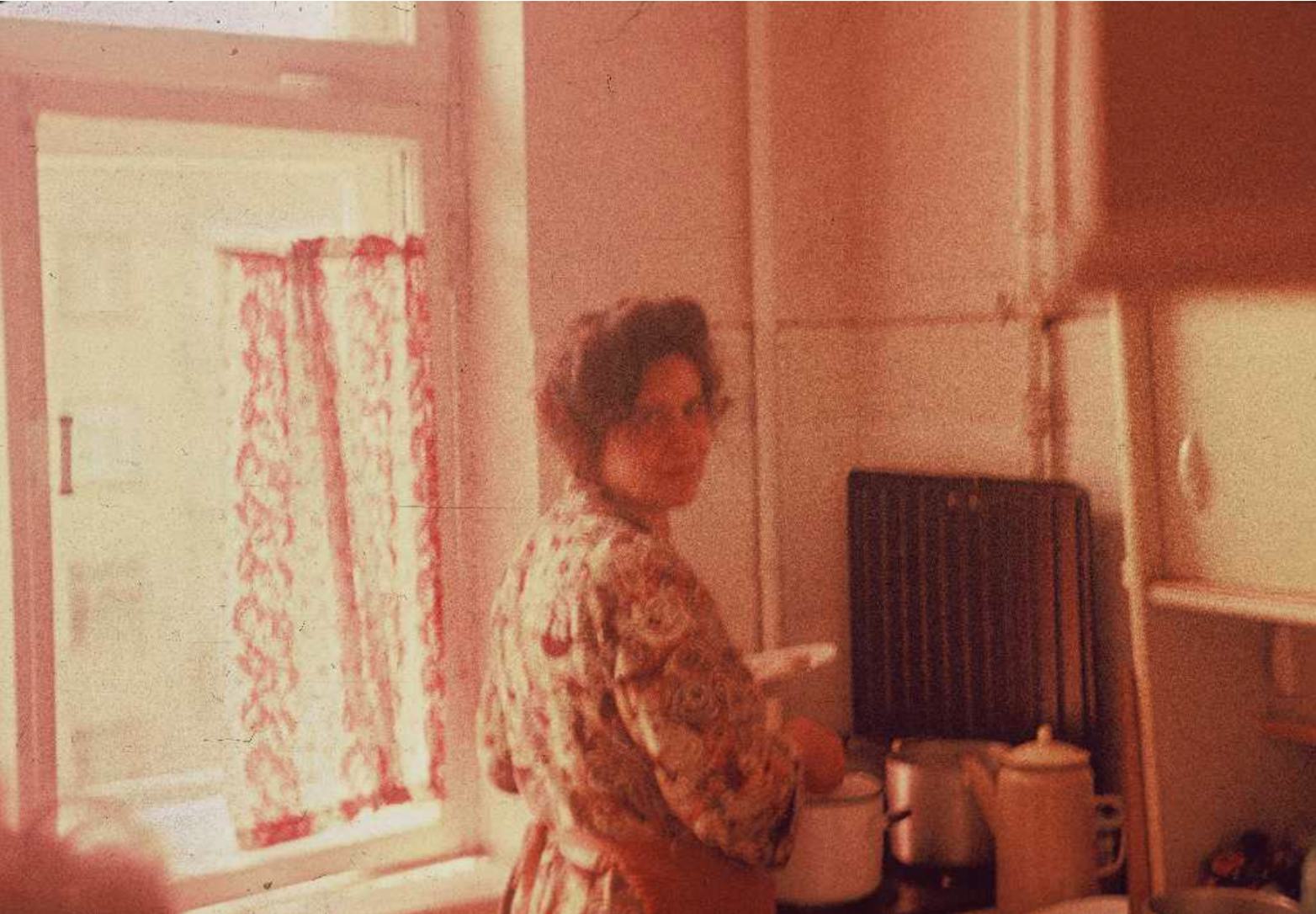

Yet her own family came first, and when in 1953 she gave birth to her only child Mykola – whom she affectionally dubbed “Koliunia”– she devoted herself to her loved ones with the self-emptying love that came to define her in the eyes of everyone who knew her. On rare occasions of absence from the family home – visiting relatives in the Caucasus or going on a painting trip with fellow artists – she would return to a mountain of unwashed dishes in the bathtub left by her husband and son, and silently, without reproach, would begin putting her house in order again.

Mykola was a sickly child. His Armenian heritage is visible in the olive shade of his skin, his full head of dark hair, almond-shaped eyes, sensuous lips. Friends describe him as a gregarious, if impractical character, whose interest in philosophy and romantic sensibility imbued the most sober of his works with an expressionistic, esoteric quality that barely passed muster in committees. Creatively gifted from an early age, he often found it difficult to follow the brief set by the Soviet establishment as early as art school, but his father’s position at the Art Institute ensured that there were no barriers to his entry. A brief early marriage and a summer of love spent in the workshops on the grounds of the Kyiv Monastery of the Caves, one of the world’s oldest Orthodox Christian holy places, resonates through his work for the rest of his short life. Another marriage and a child followed. He was a loving father who saw himself as more of a fellow playmate than role model – a family friend remembers Vera Sogoyan coming home to find her jewellery picked apart by the dynamic duo in a curious frenzy, her best china used as bowling pins.

Mykola Chernikov and his first love. Kyiv, 1970s.

Vera died in the summer of 1986 in the wake of the Chornobyl nuclear disaster. Her only solo exhibition took place three years after her death, in 1989. The self-conscious and supportive wife did not think it appropriate to draw attention to herself and occupied one of the smallest studios in the artists’ workshop building. The door remained tightly shut, with no guests allowed. I imagine her sitting in meditation on a warm spring afternoon, the air scented with wildflowers and turpentine, her face serene, crowned by a sunlit halo, levitating an inch off the ground. A few precious hours between family responsibilities, an image forming in her mind.

Vera Sogoyan in the 1980s.

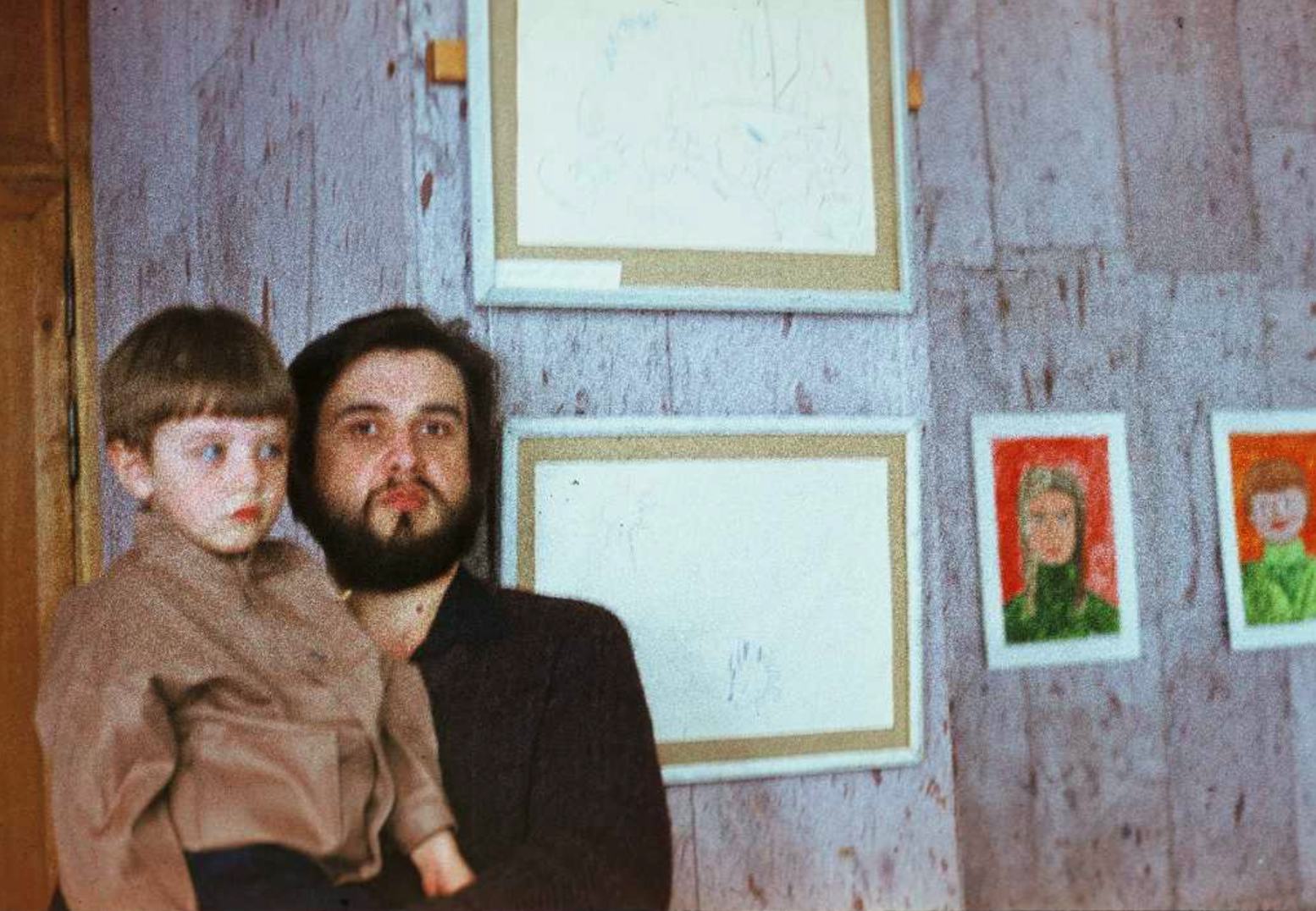

Mykola Chernikov with Misha at his first art exhibition.

The absence of Vera Sogoyan was felt painfully by all who knew her, none more than her son, whose chronic health issues exacerbated without her constant care. Medication was forgotten, diet and sleeping patterns became haphazard once again amid more coffee and endless cigarettes, and it wasn’t long before Mykola’s mental and physical health began to deteriorate rapidly. His childhood friend, a fellow hereditary Soviet artist, told me that Mykola’s illness – likely the result of an infected cut that led to a liver condition – affected his colour perception. As it progressed, the world appeared to him increasingly in shades of yellow, just like it did for Van Gogh.

Chernikov’s oil sketches and paintings are bathed in the desperate beauty of the golden hour, with heightened colour combinations that verge on the psychedelic, brimming with the painful detail of natural abundance – cloud formations, blossom, wheatfields, faces in the rocks, gilded church domes afire with sunrays. They are laden with the presentiment of impending disasters – nuclear Armageddon, empire’s fall, personal losses, the failure to capture treasured moments slipping away. In later years, they reflect his growing interest in esoteric and occult ideas that circulated more freely during the Perestroika period and in the early years of independence as society searched for new values as Communism declared its ideological bankruptcy.

Mykola Chernikov, ‘The Sacrifice of the Chornobyl Firemen’ (1987)

In 1991, the USSR broke up into its constituent 15 republics, and Ukraine became independent. In this turbulent time, few people noticed a young artist’s exhibition in the Vernadsky Scientific Library (the building appeared in the recent HBO series ‘Chernobyl’, one of several Kyiv locations that stood in for Soviet Moscow). State commissions were a thing of the past, the free art market in its infancy. European dealers flocked to the former USSR in the early 1990s and scooped up works by Soviet artists for a pittance to feed a brief vogue for Socialist Realism in the West following the fall of the Berlin Wall. Vera Sagoyan’s vibrant works became a source of income for the family – very few remained in my archive. Volodymyr Chernikov passed away not long after the lowering of the red banner, in the spring of 1992. On October 22nd 1996, after a violent spell of mental and physical ill health, Mykola Chernikov followed. It was his 43rd birthday.

Father and son: bored in an arts committee meeting

Side by side in Baikove cemetery.

I showed Mykola Chernikov’s work to an art historian at the Courtauld Institute. She said: “This reminds me of the covers of Soviet science fiction books from the ‘70s”. It seems that the liberal West’s critics were no more impressed than their Soviet counterparts. Around the same time, an academic friend asked to feature Chernikov’s ‘Construction of a Church’ (1972) on the cover of his latest philosophy book, having espied it on my mantelpiece in Oxford – a fitting tribute, given the artist’s own philosophical predilections.

I gave Misha a copy of the elegant hardback. He told me that his father used to write a lot, covering pages and pages of loose sheets with writing on ‘philosophical matters’, which he carried with him wherever he went, earning the nickname ‘professor’. His father liked G.W.F. Hegel and Hrihorii Skovoroda, the itinerant Socratic philosopher of Ukrainian Cossack origin who wrote: “Our kingdom is within us… and to know God, you must know yourself” – thus encouraging every person to find their true calling, their “native labour”. One day, Mykola Chernikov left his satchel, containing years of handwritten notes, on the tram. The only piece of writing by Mykola Chernikov that I managed to trace was his short tribute in the catalogue of his mother’s posthumous exhibition. He writes: “When in that final fateful day I asked her: “Mama, what was the happiest time in your life?”, she replied: “When you were born.” To share one’s joy is, perhaps, the best thing that an artist could do. Vera Sogoyan strove to do just that.”

Oil sketch by Mykola Chernikov painted in one of the happiest summers of his life. Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra Monastery workshops.

The history of a family of artists that I managed to assemble is brief, spanning half a turbulent century – it can be told succinctly, dispassionately: they lived, they produced artworks and enjoyed some success in their lifetime, they died. The body of work that they left behind does not begin to capture their complexity as people, nor does it reveal their private struggles. I do not really know them – the sense of familiarity attained through years of sitting at their ghostly table is an illusion. And yet the ghosts had a lesson to teach me. The kaleidoscope of images they passed on hints at an intangible quality of merit that lies not in the fact that they were artists, but that they were family.

For years, I thought that my failing lay in my inability to shine a light on the artistic legacy of the Chernikovs. Now I understand that perhaps their greatest achievement lay in being human: living, striving, loving and supporting one another. It is this legacy of small everyday kindnesses that continues to speak to me from the page, encouraging me to acknowledge those closest to me and to notice every precious change of light.

All photos reprinted with permission from the Chernikov family.

Myroslava Hartmond is a Kyiv-born, Oxford-based curator, art advisor, and creative consultant with a particular interest in the uncanny and bizarre. Since 2015, she has been an associate curator of the HR Giger Museum in Gruyère, Switzerland. Her projects aim to shine a light on dark places. Myroslava recently found her Orthodox Christian faith again.

Discover more from Myroslava Hartmond.