The Urban Monastery: Faith, Contemplation, and Architecture

What creates a space of stillness in the places that we inhabit?

What creates a sense of contemplation?

Architecture shapes us in more ways than we know, and it plays a huge part in who we are as people. With each step in my architectural education, a beautifully simple realisation that I had during the summer before my studies began became ever clearer to me. This was that the physical, tangible existence of the built world has the ability to truly impact an individual’s life – not just in an overly conceptual way, but in a profoundly meaningful and spiritual way. At around the age of 14 or 15 – which happened to be the time my faith in Jesus became something I really started to explore for myself, having grown up in a Christian home – I decided I wanted to become an architect. A few years later, after getting my acceptance letter to study architecture at the University of Nottingham in the U.K, I had that very realisation, that architecture had the ability to really shape people. And in realising this, I discussed with a best friend of mine during that summer how amazing it would be if you could design it in such a way that people could physically and spiritually feel the presence of God. And from that moment, that became my goal for architecture school and beyond, to design spaces for people to encounter the presence of God in one way or another.

The urban population of the world is rapidly growing, rising from 751 million in 1950 to 4.2 billion in 2018. With 55% of the population already in urban areas – and with this figure expected to reach 68% by 2050 – the design of our urban spaces becomes ever more important. In today’s urban society, that seemingly never sleeps – at least until the Covid-19 pandemic forced most of us to a halt – I believe that architects, spatial designers, and the many shapers of the built urban world have a huge responsibility to the people that inhabit it. This is a responsibility that perhaps has always been necessary, but that today and then tomorrow should posses a much higher level of importance. This is, put simply, to integrate rest, peace, and moments of contemplation into the (beautiful) chaos of the city. Now this isn’t to say that the buzz of the city is a bad thing – in fact, I personally feel the complete opposite, having had a love affair with New York City for most of my life – but I believe the sometimes relentless buzz can become a problem when the city isn’t designed with a balance in mind. Whilst this balance comes from a number of different places depending on where you are in the world, including social and cultural differences in day-to-day life, I want to question specifically the balance that architecture provides in a western culture.

Let us take New York City as an example, the city that quite literally never sleeps. To me, what makes New York City New York City is the people and the architecture (… and the dollar slice … and the bagels … and the honking cars… the list could go on, but for the sake of the word count of this article, let’s focus on ‘people’ and ‘buildings’). The people are passionate, outgoing, and full of energy, and I believe that this could be partly due to the design of the city itself. The grid layout that is synonymous with the relatively young city is by no means a new concept. In fact, ‘The Making Of Urban America ; A History Of City Planning In The United States’ points out that the grid as a concept is “the most pervasive city design on earth [found in] Italy and Greece, in Mexico, Central America, Mesopotamia, China and Japan.” In New York City’s case, it was designed to combine “beauty, order and convenience,” as well as being a convenient way to maximise profits. Could it be that it is the supposed efficiency of the layout that is partially responsible for the apparent energetic override that is present in the city and its people? I’d argue that yes, it is. Of course, you need to take into account the population size of a city, the transport links, the city’s functions, as we can’t assume any city built around a grid will have the same buzz as New York City. But compare a similar sized population, London, where you meander from point A to point B instead of walking down a rigid straight street, and immediately, simply because of the layout of the roads, the physical ‘chaos’ and buzz of the city is diminished (I have lived in both, and can say from experience that this is true). But does the buzz of city living – whatever the city – become too much sometimes? Perhaps.

Even I – and I want to stress just how much I love New York City here; I am someone who literally hums Sinatra’s ‘New York, New York’ when I walk along the streets of Manhattan, wide-eyed and bushy-tailed – can admit that sometimes you just need a break from it all! When the buzz of a place is infinite without any moments of relief from it, people will break – we are only human! And that is okay! Whilst I can think of countless places of relief within the city that I love, I think more can be done, and that is why I chose to explore this theme in my final year design project. The things that give a city its buzz can sometimes manifest themselves inside people as stress, anxiety, and depression – feelings which I think are generally thought to intensify in densely populated urban areas. And these intensify yet again in a culture often run by social media and technology, when our brain has very little space to switch off, and where mental health awareness is quite rightly gaining momentum. If this is the case, and if we can agree that designers of the spatial realm are able to affect the mood, atmosphere, and function of a space – whether a room or city – then I think those shaping this space, including myself, need to realise how great their responsibility really is. Although the origins of this project were developed in 2019, before the pandemic tore around the world, I think the pandemic has helped to reveal the problem further still that I was building my project around; a lot of people simply don’t know how to rest in today’s society. So, my answer to the problem is to help by designing it straight into the spaces we inhabit, for the benefit and longevity of those inhabiting them.

A Journey Through The Urban Monastery

‘The Refectory: An Urban Monastery’, was an exploration into answering the question “what creates a space of stillness and contemplation in the spaces we inhabit,” and applying the findings to the generic high-rise typology. The scheme aims to sit somewhere between a spa or retreat and a religious monastery, not aligned to a particular religion or religious use. However, monastic traditions and conditions have provided guidance for the design of The Urban Monastery, in both the programme and the physical design of the building. In places I have intentionally altered these traditions within the design – most noticeably being the vertical design of a typically lateral typology – with the goal of pushing the boundaries of what both the monastery and the high rise as a typology are capable of spatially. As I mentioned before, whilst important even before the Covid-19 pandemic, the themes of reflection, contemplation and rest are more important now than ever, and I have been exploring how different elements of the design can alter one’s perception of a space, transforming it from just a room with a function, into something bigger – physically, mentally and spiritually. With ‘rest’ not designed into our cities, The Urban Monastery tackles this through the programme – as an urban monastery, an adapted version of the traditional monastery that blends the monastery we all know with a form of retreat, and aims to fit into shorter periods of time within our urban life – and through the structure of the building, that explores the globally untapped potential of the timber high rise in a city of concrete, brick and glass. The priority in my conceptual scheme was most definitely the design, with countless revisions of the tiniest details throughout the spaces all trying to enhance the feeling of rest and contemplation in one way or another.

So, for now, let’s take a journey through the Urban Monastery.

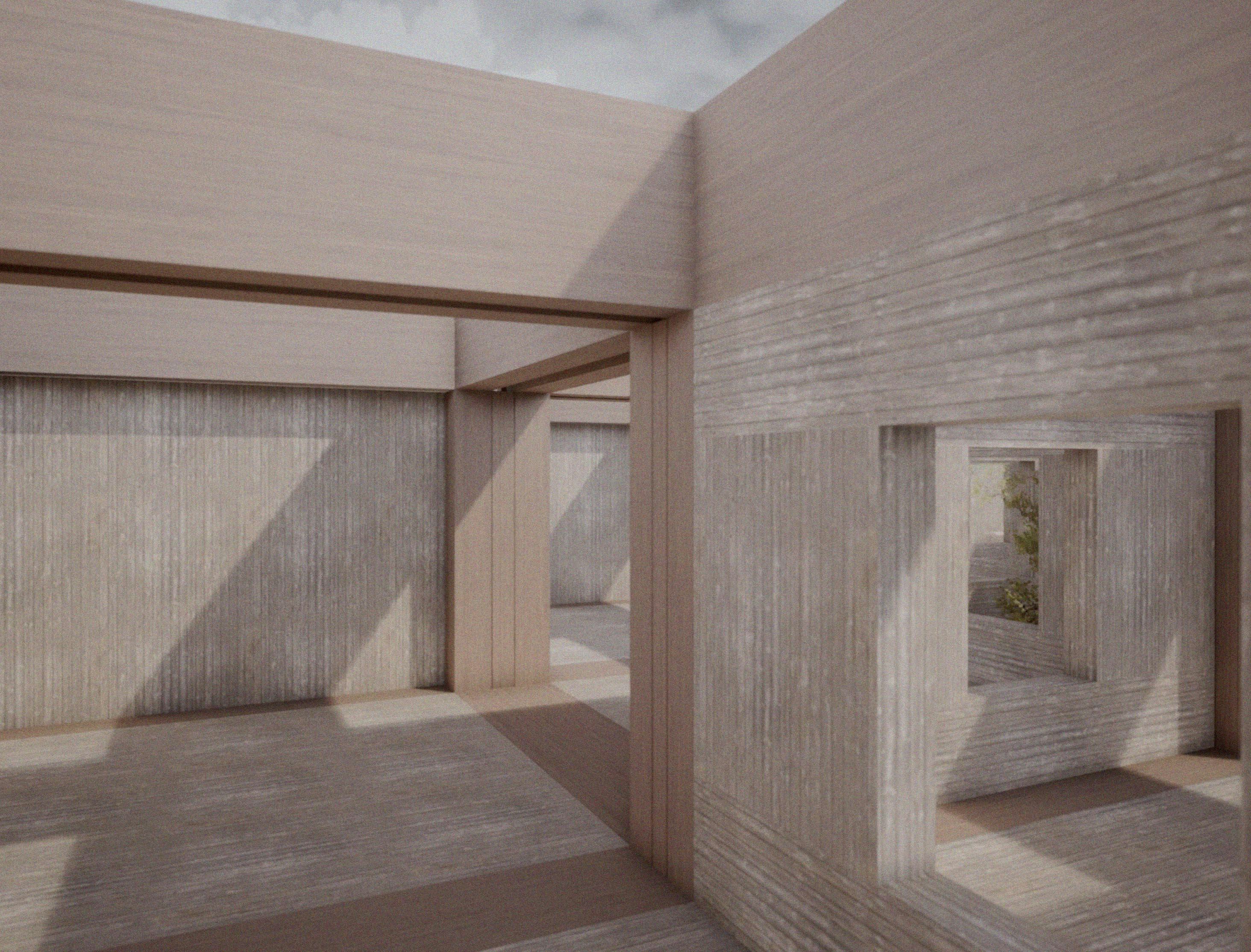

Upon entering the monastery, you step through the seemingly infinite timber grid and gaze upwards at the space above you, the blurring of your own scale in the world begins, and you are taken away from it. You journey around the perimeter of the open space to the stairs placed within the grid at the end of the corridor, and weave upwards through the building.

The corridor carries you as you walk from space to space, circling vertically, holding you as you rest, as you contemplate and meditate on turning off the noise around you, turning instead inwards. You are walking within the structure, meandering slowly upwards towards the sky.

You peel off from the corridor, stepping onto and through the grid again, then stepping down onto the single step at the entrance of your room, a gentle feeling of safety washing over you as you sink lower towards the ground, where you close your eyes.

On waking, you continue meandering upwards, stepping out to the world for a moment. Here you gather what you need, whilst letting go of what you don’t.

Back inside, the sunlight spreads over the countertop, delicately suspended within the space left over by the timber grid, the blurring of scale slowly presenting itself to you, an ambiguity lying between this fragile form and the oversized column.

You are aware of sitting within the grid, not just on it, but within something bigger than yourself, its oversized and ubiquitous existence making you feel small somehow, holding you gently within it. Here you all come together, to eat, to laugh, to learn, before continuing onwards on your journey through the day.

The white tiles in the washroom blur together with the cloud of steam that surrounds you, gently cleansing your skin, lifting you away.

Stepping through the shadows, you emerge into a break in the stubborn timber grid. At times you come together here. At others, you come alone. A space to pray, to worship, however you need, the vastness of the space and the light streaming in from above drawing your gaze upwards, your focus on one thing alone.

When you are ready, you emerge out into the walled cloister placed atop the monastery, your journey halted only by the sky above. The warm sunshine that greets you sends shivers up your spine, the clouds gently blowing overhead, the tap of the weathered planks below your feet, that then shifts to the crunch of pebbles.

The continuous timber planked walls around the perimeter seal you off from the city. Your separation from the world is realised again, the sky hanging above you, the city audibly below but hidden from view, simultaneously in the centre of it all whilst detached from it. A new blurring in scale occurs, this time between the sky and the structure. The sky’s vastness pulls you up, away from the distractions of the city, and the distractions of your mind, leaving only you, still held gently within the timber grid.

Working within my studio, ADS5, at the Royal College of Art allowed me to design in a new and extremely freeing way, by designing my project in reverse. This comprised of exploring ambiguous spaces based solely on our own design intuition, using interior views and hand drawing to truly focus on the pure design elements of the space. In taking the themes of rest and contemplation, and without the need to design a programme or function for the building to start with, I was able to focus solely on what it was about every detail in my building that could lend itself to an atmosphere of rest and contemplation, whatever the programme. This wasn’t an exercise of ‘form follows function,’ and it wasn’t ‘function follows form,’ but in fact it was nestled somewhere in between in its own little world.

The structure of the large CLT (cross laminated timber) elements was something I spent many months trying to get right – the proportions, the dimensions, the texture – and it held the most literal metaphor to representing my faith in God in the scheme, which I will explain through the lyrics of a song a little later. The implementation of an exposed structural grid isn’t new, however I would argue that it is very rare to be 100% visible throughout the entire building – in fact, I am yet to see it for myself. Architects like Richard Rodgers are famous for turning the building ‘inside out’, showing the services and structural elements on the outer skin of the building, but internally, perhaps due to the buildings function, the structure is not often as visible. With walls, floors, and ceilings, it is understandable that the structure is usually covered up my other fragments of the design. But the beauty of CLT is that because it is so thick – the columns in my scheme are 600x800mm – and able to span so far, you have a huge amount of wiggle room to house your floors, walls, ceilings and services, and still have space left over to reveal the columns and beams in their raw state, as well as creating thermally comfortable spaces. So from the start, I decided to reveal the CLT grid throughout the entire interior and exterior of the tower, and this was relentless throughout the design process.

Whilst walking through the building, whether entering at the ground floor or going from corridor to room somewhere higher up, you walk within and on the exposed structural grid. Floor panels are held in-between each beam, the beam left flush with the floor, which results in the beam also becoming the floor you walk on. There are moments where the inhabitants have to step up to or down in level, stepping from the structural grid, onto a floor plate that is placed just one step above or below the floor level in the previous space. These small moments are encouraged in the transitions between spaces, most commonly when reaching a space of rest, for example a bedroom, or outdoor or eating space. These are meant to cause an awareness of being held within the ubiquitous grid.

And this is where we find the lyrics of the song I spoke about previously. In growing up going to Sunday school at my home church, we used to sing a song that had the words “and he holds us in his hands”. Of course, we would do actions to this (because who doesn’t love actions with their worship music), lowering two fingers into the palm of our other hand, as though we were the standing up fingers, and God was the palm of our hand, our creator, gently holding his creation in his hands. In The Urban Monastery, you are delicately held, floating within the grid, part of something much larger in the universe than yourself. A little cheesy? Sure, but who does’t love a little cheese?

The changes in level occur in the ceilings too, with transitions from low corridors to double height rooms encouraging a sense of awe as you gaze upwards. The size and scale of the space in comparison to its users and the structure running through it was purposely toyed with throughout the building, creating a blurring of scale at times. This was because so often secular buildings are either scaleless, or perfectly scaled to the human, and whilst you would think this makes sense seeing as humans are using it, I believe it results in uninspired and stale spaces. I wanted inhabitants to notice when they were walking through the structure of the building, to create a moment of contemplation. I wanted them to realise this huge endless grid is supporting them as they walk along the winding corridor amongst the clouds. The corridor was fundamental to the monastery as a typology, and it is something that slowly became the secondary focal point of my scheme. It’s ability to link spaces together is obviously extremely important for functionality, but it’s importance lies in it’s ability to loop endlessly around the cloister at the centre of a traditional monastery – or in my case, looping upwards and around the building – providing a timeless experience that enhances themes of positive solitude and reflection for an individual as they meander onwards.

Finally, the detailing of the furnishings was something that I wanted to use to add to the blurring of scales, using fine and fragile materials to contrast with the dense, heavy timber structure surrounding it. Copper and gold colouring are used for the window frames and the handrails throughout the building, as well as white cast marble and concrete as suspended countertops and stair toppers, standing out from the monotone timber colouring that spreads seemingly infinitely elsewhere. The hope is that this material contrast adds to the tension already created between different structural scales, by the fragile benches, the suspended countertops in the refectory, and the simultaneously lightweight yet solid steps that are scattered around the monastery that cater to the level changes between spaces.

The Urban Monastery is a first step for me, an experiment if you’d like, towards learning what it is that creates spaces of rest and contemplation in today’s society, and how this links in with my faith in Jesus Christ. The question I had as a boy – ‘is it possible to design a secular space where people can physically and spiritually feel the presence of God’ – is still both extremely obvious and completely unknown to me. We know there are tricks in spatial design, for example, the larger spaces within the nave of a church stretching upwards, taking your gaze with it to create a sense of awe, and therefore reflection on God our creator. But what I am desperate to find out, and what I’m sure it will take a lifetime to figure it out, is how to translate that atmosphere into the functional, day-to-day spaces, that aren’t necessarily designed for God in the way that a church building is, but that somehow reflects His presence and His glory. Is that even possible? To design all space for God? I hope so!

In working through this project, I realised that it isn’t fully about the physical atmosphere created by the room, but by the impact that the design of the space has on an individuals actions within the room. Contemplation is crucial for us as a people; it is how we learn, it is how we grow, and I think it provides a space for us to meet with God amongst the chaos of the routine day-to-day tasks. And if I can design spaces that encourage a state of contemplation through the tangible built world, even just for a second, I will consider that a job well done.

Jonny Ryley is an Architectural Designer and Photographer based in New York City, and recently completed his Masters in Architecture at the Royal College of Art in London. He was born and raised in a Christian family the U.K. and was baptised in 2017. He worked at COOKFOX Architects before his Masters, and has just relocated back to New York City. He is now exploring new ways to combine architecture and his faith in his work. Instagram: @Jonny_Ryley

Discover more from Jonny Ryley .