Imagine for a moment that our skin was a transparent membrane which revealed the inner workings of the body. That we humans had been designed in a way that left the mechanics and chemistry of our anatomy in plain view – much of it the direct result of our habits.

Would we become more conscious of what we ate if we had to witness the process of digestion, for example, the gargantuan effort our digestive system had to make as it broke down the trans fats and sugars contained in our fast-food feast?

Would we be more motivated to exercise if we were to observe the jelly-like subcutaneous fat jiggling under the skin, while visceral fat slowly built up around our vital organs?

The menstrual cycle, no longer veiled in mystery beneath soft folds of skin, but manifesting in plain view – would it become less of a taboo?

How different would sex be if we no longer assessed our potential mate by surface appearances and scent only, but rather, could read their anatomy from the inside out?

And if we could see for ourselves the effect that so-called stress – the failure to control our thoughts and feelings – had on our bodies, would we be more likely to incorporate meditation into our daily routines?

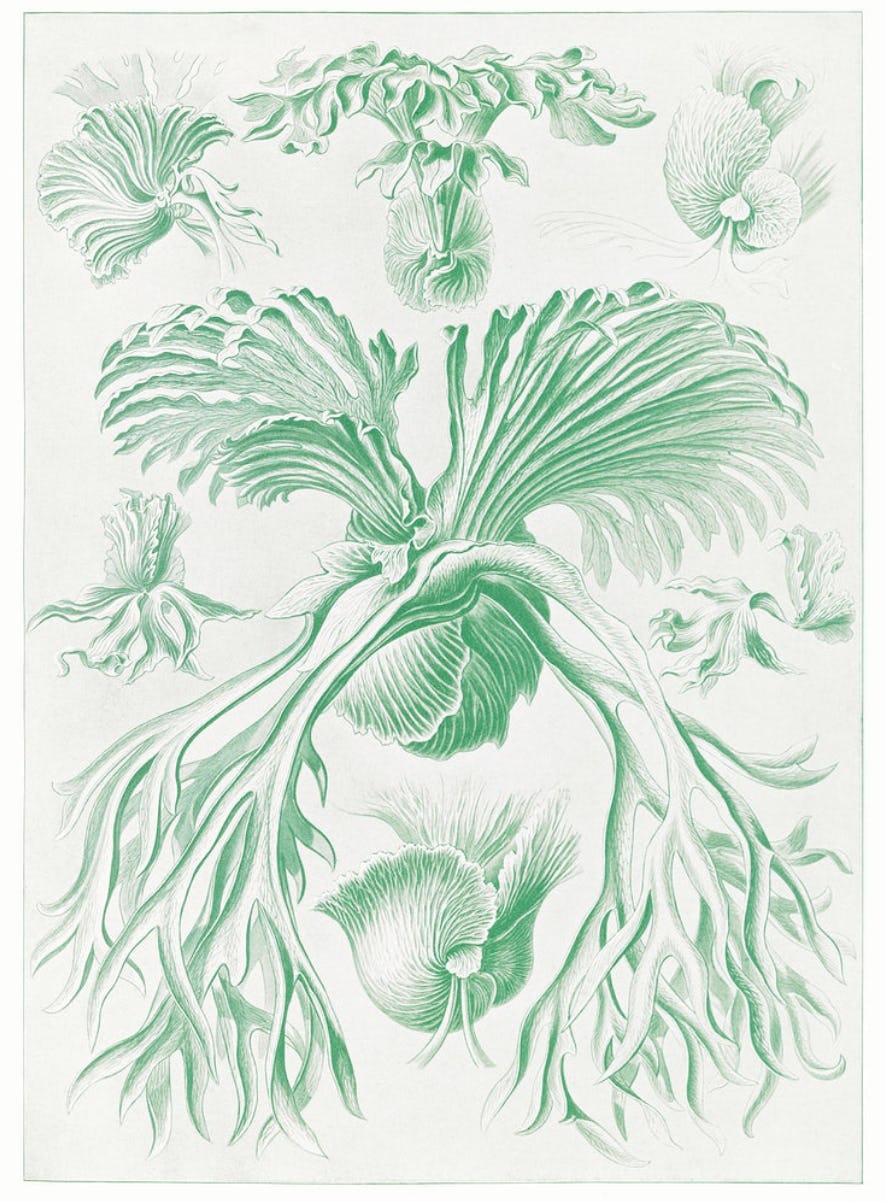

The opaqueness of our flesh is a blessing. It keeps us blissfully unaware of a plethora of happenings within the walls of the house that is our body. When in the mid-nineteenth century German scientist Ernst Haeckel sought to name a new discipline that studied the relationships within biological systems, he opted for the term ‘ecology’, which derived from the Ancient Greek word for house. Haeckel was a zoologist, artist, writer, and later in life a professor of comparative anatomy, whose illustrated book series Art Forms in Nature (1899-1904) had a profound influence on the Art Nouveau movement in art, architecture, and design. The ‘new art’ took its inspiration not from historic styles, but directly from nature. Defined by the whiplash line and ornament that favoured organic forms and depictions of the female body, it was imbued with the decadent erotic tension of the fin-de-siècle metropolis. Haeckel’s lithographs, though immune to such excesses, shone a light on the beauty and endless variety of the natural world, especially forms of hitherto unknown marine life. Far from being a simple cataloguing exercise, the volumes presented a worldview, according to which all of creation was beholden to the same laws of symmetry and levels of organization.

At its core, ecology is the study of relationships within a closed system, and while today we associate it primarily with environmental science, the term is also used more widely, as in ‘internet ecology’, ‘corporate ecology’, ‘human ecology’. We intuitively associate it with notions of equilibrium, balance, cleanness, interdependence, as well as understand it to relate to the overall quality of something. Is it time that we spoke of the ecology of the body?

After all, our bodies are ecosystems, at once fragile and resilient configurations of closely integrated parts – organs – conditioned by genetics, environment, nutrition, physical regimen, as well as emotional and psychological patterns. Could this approach stimulate a more holistic attitude towards our wellbeing?

Our skin may modestly disguise the routine operations of the body, but when something does go wrong, we are promptly notified by pain and other discomfort. All too often, prompted by conventional medicine, we isolate the offending part as a problem in itself, without stopping to consider the health of the ecosystem. What’s more, when in pain, we are likely to prioritize silencing that signal. Readily satisfied by the offer of a ‘treatment’ that simply addresses the unpleasant symptoms, rather than the root cause, we reach for our painkillers at the onset of yet another bad turn. Again and again, we refuse to decipher the message that our body is sending us in the form of pain, which in many cases has an underlying emotional or psychological cause.

By contrast, Chinese traditional medicine has long viewed the body as a system of correspondences, whereby each of the five major organs – liver, heart, spleen, kidneys, lungs – is also the primary seat of a particular emotion. Perfect health is equated with a perfect balance between them and the unobstructed flow of life energy or qi through the meridians (energy pathways of the body). For example, the liver is the seat of anger; despite its bad reputation, anger serves a purpose when mindfully directed in a critical situation (think Jesus expelling the money changers from the Temple or the female of the species protecting her young). However, when out of balance, anger can literally burn the body from the inside and create a toxic environment for everybody around (think road rage and domestic abuse). Other traditional systems offer integrative approaches to viewing the human body, such as the chakric system in Ayurvedic medicine known to the Indian subcontinent for thousands of years and steadily gaining traction in the West since the 1960s.

In recent years, Western medicine has become more open to studies in psychosomatic medicine, an interdisciplinary field exploring the relationships among social, psychological, and behavioural factors, and bodily processes, and quality of life in humans and animals. In other words, the fact that some conditions – such as chronic back pain or menstrual dysfunction – appear to have no discernible physiological cause can no longer be ignored even by the staunchest empiricist.

Most of us who have struggled with chronic conditions and sudden, inexplicable aches and pains know that our urgent search for immediate relief often puts us on a deeper journey towards healing. Far from offering easy solutions, it encourages us to consider the body not as “the numb whole with painful bits”, but rather as a system that must be once again brought into balance, a conscious system that “speaks” to us in the language of pain and discomfort, the only language that our jaded, busy selves will not ignore.

Often the most difficult first step is to “feel into” the pain and establish a line of communication with the afflicted part. The accessible, well-known works of Louise Hay and Lise Bourbeau were a useful starting point for me when I first recognized the need to master the symbolic language of the body. To have the courage to peer beneath the veneer of skin and to acknowledge the problem without hating the ailing part is the necessary first step to recovery.

Guided meditative journeys into an area of our body, which in fair-weather conditions we might not have the courage to explore, are another healing technique that has brokered sudden breakthroughs. What hurts and fears and worries and resentments lurk in our hearts, our lungs, our stomachs, our kidneys, our wombs? Unheard, unfelt, they manifest as ulcers, lesions, polyps, tumours, stones. To purge the system of toxins – through crying, journaling, creative or talk therapy, or the sacrament of confession, and finally through forgiveness – is the second step, without which the balance cannot be restored.

Chronic conditions that arise in organs associated with expression and creativity – typically the reproductive organs and throat, corresponding with the second and fifth chakras – may be the result of a systemic stifling of one’s creative impulses, feelings of not being ‘entitled’ to an artistic practice due to professional or family commitments, a lack of time and energy, or fears of inadequacy and failure. I did not even realize that I had this problem until a friend casually forwarded me the audiobook of Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way. In the linguistic wilderness of a month-long business trip to China, I was able to work through the first weeks of the creative unblocking course with uncharacteristic diligence. I adopted the practice of Morning Pages (three longhand pages of journaling done first thing in the morning to drain the brain) and faced every critic – including myself – whose judgement had me completely abandon creative writing in favor of scholarship and journalism by the time I was in my early 20s.

This gradual unfettering of my creativity took on a new momentum during the lockdown months. As a previous chapter of my life as a gallerist ground to a halt, and the initial shocks subsided, I was able to learn once again to live at a slower pace and to trust my dormant instincts. A spell of ill health encouraged me to reinvent my daily routine, which now included prayer, meditation, yoga, a better diet, much less coffee, and a regular writing practice. Poems whispered themselves to me, while a novel I’d been dreaming up in my head for years finally started to materialize on the page. This new practice helped me to reclaim an important aspect of my inner self that I now knew I needed to break through to the next stage of my development. And while a return to full-time work may mean that this practice is not a daily one, I intend to hold on to this thread.

Our skin may mark a physical boundary between our bodies, yet we are united by ties of blood and tribe, whether in the conventional sense or through the ever-widening potential for selective connectivity associated with our digital age. The ecology of our sovereign bodies is affected by our activity in the realm of human ecology, something that has been brought into sharp focus by recent global events – political, economic, epidemiological. Shaped from the start by the people who are closest to us (our parents, carers, siblings) and by the places where we may have lived, studied, worked, the body as ecosystem is closely related to a wider framework. Some of those people and places fill us with love, while others leave welts and bruises on both body and soul.

We cannot change the past, but we can change how we relate to it. We are neither immune to external challenges and the stress that accompanies our attempt to rise to them, nor are we free to shake off our responsibilities to (and dependence on) other people, be it our children or our boss. However, it is in our power to define our boundaries to the best of our ability: to learn techniques that allow us to cope with stress, to limit exposure to the more toxic elements of our human ecosystem, and to carve out much-needed time for rest and relaxation (hopefully, without our phones…). In sum, ‘choose your battles’ and ‘keep your dear ones close’ may be suitable modi operandi in a state of perpetual catastrophe.

In the great lottery of creation, we each have been presented with a body to make our home. And while factors of genetics, race, gender, class, and location converge differently for every individual – making some lives ostensibly rosier than others – the process of crafting the ecology of the body is one that depends on a conscious, continuous effort on our part. In other words, staying well is hard work, but it needn’t be exhausting or a chore.

On a long enough timeline, incremental improvement is always more effective than an ‘all or nothing’ approach to diet, exercise, and mental and spiritual health. We needn’t possess the ability to see through skin to start making healthier choices, or wait until something hurts to open our hearts and embrace our passions. And while bouts of illness or another life challenge may give us a much-needed nudge in the right direction, every body is a system that contains within it a unique blueprint for its very own iteration of wellness.

The term “ecology” (German: Oekologie, Ökologie) was coined by Ernst Haeckel in his book Generelle Morphologie der Organismen (1866); it was based on the Ancient Greek οἶκος (oîkos, “house”) + -λογία (-logía, “study of”).

Myroslava Hartmond is a Kyiv-born, Oxford-based curator, art advisor, and creative consultant with a particular interest in the uncanny and bizarre. Since 2015, she has been an associate curator of the HR Giger Museum in Gruyère, Switzerland. Her projects aim to shine a light on dark places. Myroslava recently found her Orthodox Christian faith again.

Discover more from Myroslava Hartmond.