My grandmother loved flowers. Originally from a farm in South Korea, she knew how to tend to things, how to get them to grow and thrive. You couldn’t miss the garden she planted out front, the colorful flowers and little figurines welcoming you to the home she shared with my grandfather.

On the day she died, I drove to that house and parked in the driveway. I couldn’t bring myself to walk past the flowers and into the house, the way I’d done so many times before. Knowing she’d touched the very things in front of me, cared for them, placed each little figure just so and roped plants together so they would grow upright—it ripped me up inside. It was too tender for me to process, this idea that she’d made all of this come to life and now she was gone.

Instead of going inside, I stood in front of the garage, hiding from my family and wishing I could rewind time, opt into a different reality—namely, one in which she didn’t spend most of her life working in laundromats, inhaling chemicals that would scar up her lungs and eventually prevent her from breathing. One in which she was healthy, happy, and still very much alive. One that didn’t end with us here.

*

Just a few months before the pandemic started, I sold all of my furniture and moved from California to Texas. My parents were living in Belgium, and their house in Central Texas sat empty. It seemed like the perfect way to save some money and then embark on a year full of travel and remote work. I booked a month-long trip to Buenos Aires to start.

I certainly never imagined I would stay in that small Texas town, over an hour from Austin and far from any communities I’d invested in as an adult.

Yet the pandemic had other plans for me. I’d lost my job a few months before, in December 2019, and I threw myself back into freelancing, determined to still follow through on my goals to travel. However, as the pandemic took root in America in March 2020, I watched as my business withered and my future plans got canceled, one by one.

At first, I experienced a surge of purposefulness. There’s nothing more motivating to me than a challenge, and living alone in the middle of nowhere felt like the ultimate one. I took it as an opportunity to write the novel I’d always wanted to, to study for the LSAT exam, to work on patterns within myself I didn’t like.

That went well for a while but at some point, I grew anxious and lonely. The drastic decrease in social stimulation began to take a toll on me. Once, I went a week without any actual human contact. Going to the grocery store became one of my favorite things to do. There, I’d spend time browsing the shelves, looking at unfamiliar items and getting some much-needed time out of the house.

I’ve always been pretty introverted, and I didn’t realize until then how many of my needs were met by hovering on the periphery of social spaces. Gone now were the days of hanging out and working from coffee shops or reading in a crowded park. I felt untethered, invisible. I questioned my decision to be single. I wondered if I should move in with a friend, just so I’d have some built-in human interaction.

The one silver lining was that living in this small town meant that I now lived a short drive up the highway from my grandparents. About once a week, I’d go and visit them. Many times, they—and sometimes my aunt and cousin—were the only people I’d see in a given week.

My grandma had long been one of my favorite people. I always felt so comfortable being around her. As someone who grew up moving around every few years, I pick up fast on who or what feels like home, and she was it. I loved her laugh, her style, the way she could mend familial arguments in her gentle, soft way. I loved the way she cared for our family, namely through feeding us. She always had a warm plate of food ready for me, and she was guaranteed to send me home with way more leftovers than I could eat on my own.

As desolate as I often felt about the pandemic, I remember wanting to hold on to the good moments I shared with her, too. I didn’t want to look back and see only the bad or the hard things. I wanted to also think about the spring roll party we had one afternoon, when she put everyone to work assembling and rolling their own food to take home. Or the time the women in the family met at her house and stuffed mandu, a Korean dumpling, and she fried them up for us. She even made special gluten-free ones for me, as a treat.

It was great to be able to see her more than I’d ever been able to before, but there was also this: her cough had taken root by then. I can’t remember when exactly it started, but she complained about it during the pandemic often enough for me to take note. It was hard to say how serious it really was, though. She’d been talking about various ailments or aches and pains for years.

Maybe I didn’t pay enough attention, and I missed the signs that this cough was different than the other issues she’d had. Maybe my lack of attention is why I ultimately felt so unprepared for what happened.

*

The cough continued. At some point last year, I went over for my weekly visit and saw a printout laying on the coffee table. The words at the top read: “Pulmonary Fibrosis.” My chest tightened.

She told me the doctor had diagnosed her, and this condition would be what killed her. Because of her age, there was nothing that could be done to help her. She was too old for a transplant to make sense anymore. The primary goal would instead be to mitigate and manage any symptoms she had going forward.

I resisted this news. I wanted to wave it off, to think it wasn’t a big deal, but the diagnosis seemed to send things downhill. She slept more during the day and seemed tired even when awake. An oxygen tank became a fixture in the living room. Eventually, I rarely saw her without it.

One day, we walked to her closet together to look at her jewelry. She’d just opened the drawer and handed me her birthstone ring to admire when she became short of breath and rushed back to the living room.

“Is it that bad?” my aunt asked, her face concerned. “You can’t go a few minutes without the oxygen?”

I realized, that day, things were not going to get any better. My disposition is such that I’m always looking for the solution, the way forward, the fix. But there would be no way forward, no way out of this. I didn’t know how to make sense of that.

I’d been ignoring so much of what was happening right in front of me. She was hardly leaving the house in those days. That was easy to overlook because of the pandemic and the fact that not many of us were traveling, but there were other signals I’d turned away from. She wasn’t cooking as much anymore, something that had never happened in my entire life. I realized I couldn’t remember the last time she’d been in the kitchen when I arrived, the last time I’d heard oil sizzling in the pain or smelled traditional Korean fare.

Still, I didn’t want to fully face it. I thought maybe I was being dramatic. Things might be different, but maybe we just had to adjust to a new normal. That was fine; people had to adjust to new circumstances all the time. We would get through it.

While I understood in an abstract way that the end may have been coming, I didn’t see how it could be near. She was my grandma, always so full of life and love. She’d always been there, a part of my life. I didn’t see how that could ever change.

Our birthday season rolled around. We’d always celebrated our birthdays together, right around Thanksgiving. Her birthday was November 28, my dad’s is November 30, and I’m right behind them on December 3. Year after year, she was the one most excited about the cake, the most enthusiastic about blowing out the candles, the most full of joy. You can see it so clearly through the years in the photos of the three of us, and 2020 was no different. Her face lit up. She got so excited to blow out the candles, and my dad and I let her have at it.

The normalcy of rituals like this made it easy to hold tight to my belief that things would be fine, even as new problems cropped up. She started going to the doctor more often, asking my grandfather to take her to the ER when things felt too scary or painful. She said she didn’t feel like she could breathe, even with the oxygen at full capacity.

Then, this spring, the doctors recommended hospice care. After working in healthcare for a decade, I knew exactly what this meant, but it continued to surpass my practical understanding. She wasn’t actually dying anytime soon. She was still so full of life; I could feel it coming from her.

One of the last times I saw her, shortly after being put on hospice care, I sat in bed next to her and she looked at me. “I think I’m going to stay around a while longer, Nikki,” she said.

“Well, good,” I said. “I’m really glad to hear that.” And I was, and I didn’t doubt her. I felt certain there were still years left for us—to make food together, to blow out the birthday candles together, to make memories. To be a family.

*

Confusingly, her declaration she’d be sticking around was only a couple weeks before she died.

My parents came home from Belgium for a visit, and most of the family got together on Mother’s Day. When I arrived at her house that Sunday, she was in the bedroom with the door closed. I was told she was lying in bed. I went in to greet her, and my dad came in. She hadn’t seen him in six months. I heard her tell him she’d missed him and that she was in so much pain, and I left the room to give them some time together. I felt sad and helpless.

But then, a shift.

As we all ate together, she emerged from her bedroom, fully dressed. I couldn’t remember the last time I’d seen her get dressed like that. For months, I’d only seen her in nightgowns or robes. She walked into the kitchen, teasingly swatting at my foot with her cane as she passed me. She ate a full plate of food, something she hadn’t done in a while. She rolled her eyes at something someone said.

It was just like normal again.

I kissed her when I left and told her I’d see her in a couple of days, on the coming Wednesday. That day would be my mom’s birthday and my grandparents’ 57th wedding anniversary, and we were all going to celebrate together.

Tuesday morning—the day before we would be together again—I drove an hour out of town to Austin for a hair appointment. While there, I got a text from my dad. He said that the hospice nurse and my grandfather couldn’t wake my grandma up.

“What does that mean?” I wrote back.

He told me he didn’t know. He and my mom were on their way to my grandparents’ house to get more information and check on her.

Within the hour, he called me.

“They’re going to get morphine,” he said. “The nurse says everyone needs to come say goodbye to her within the next few days.”

It’s strange, receiving news like this while you’re doing something ordinary like getting your hair done. I felt frivolous, absurd. It felt surreal, watching people mill around me, going about their business without any knowledge that my whole world was splitting apart.

Equally strange was trying to reconcile this news with the fact that I’d just seen her a couple of days before, and she looked better than ever. She’d gotten dressed. She’d eaten a full meal. How could things have changed so drastically, so fast?

I left the appointment and headed home, trying not to think about it. My dad called me again. I felt stressed. I sent the call to voicemail, figuring I could get the update from him when I arrived at my grandparents’ house in an hour. I would see everyone soon enough.

He called me again. I answered.

“She passed, baby,” he said, his voice shaking.

Time stopped for a half-second. “What?”

“Yeah. She’s gone.”

By then, he was crying, and I stupidly told him that I was sorry, as if it were only his loss to bear and not all of ours. Then, we hung up, and I drove to her house in a state of shock, where I stood to the side of the garage, staring at the flowers I’d walked past so many times before. I stayed there until my cousin walked outside and found me. She hugged me until I felt strong enough to walk inside.

*

A friend pointed out later that the way my grandmother died is the way we all hope to: surrounded by family, at home, and not following an extended battle with any ailment or condition.

I can see that now, and I’m thankful for it, but that day all I felt was numb, stunned, and at a loss. How had something so utterly permanent happened so fast? How could I not have known we didn’t have more time together? Why hadn’t I pushed her more to tell me things about her life, about her past? Neither of us were very emotionally expressive people. Did she know how much I cared about her?

When I finally made it into the house, I sat with her body in her dark bedroom. I wanted to tell her how much she meant to me. It feels ridiculous to admit, but I still struggled with what to say. I felt self conscious somehow; I didn’t want to make her uncomfortable by talking too much about my feelings.

I settled for telling her that she was the best thing about my life during the pandemic, and I hoped she knew that.

Later that night, I asked her to come to me in a dream, and she did. I woke up feeling comforted. The next day, one of my closest friends said that she’d received several signs from my grandmother, and she asked me to look out for them: a bird, a white rose, and brightly colored flowers.

I was skeptical, but I saw all of those things at my grandma’s house later that night.

These things made me feel a spark of hopefulness beyond the grief. I felt like maybe our relationship wasn’t over after all—like she’d live forever in me if I made the effort to keep paying attention.

Her visitation and funeral were scheduled. I wrote her a letter and put it in a small cloth bag with some flower petals and other keepsakes and placed it in her casket. In the letter, I told her things I couldn’t say in person. I told her that she always felt like home to me, and I will miss that forever. I told her that she didn’t need to worry about me and that I would be okay. I told her that when I think of her now, I see her reunited with her parents, surrounded by flowers and all of the things she loved so much. I see her happy, able to breathe, feeling free.

Someone told me afterward that the reason losing her hurts so much is because I loved her immensely, and that’s something to be thankful for. “And everything that you might do for anyone else is possibly a derivative of her influence on you and your parents,” he said.

I like thinking of it that way; I like the idea that she might have an effect on people who will never meet her, through my actions. I like listening for the sound of her laugh in mine. I like looking at the tattoo I have of her on my forearm and remembering how she always thought it was so funny.

She’d bought a ton of flowers a few days before she died and for days after, they sat neglected on a table in the backyard. My aunt and I split them up, and I brought my share home. I went and bought pots and soil for them. Then I potted them and gave some of them to people I care about, so that she can live on through them too.

*

For eight days after she died, I abandoned my routine pretty much entirely. I was flooded with emotions and overwhelmed by the constant proximity of other family members. One minute I felt empty; the next, I couldn’t stop crying. Everything hurt, even songs that had nothing to do with her or memories of her.

Then, a week and a half after she was gone, after she was buried and out-of-town family had gone home, I felt a tiny pull in a different direction. That evening, I sat down with my memory book and revisited a pillar of my routine: my gratitude practice. On a typical night, I make a note of a handful of things I’m thankful for that day. Each page has a spot for five years worth of memories, so I can even compare my lists from year to year.

I wrote the year under the date at the top of the page: 2021. Then I wrote: I’m glad Grandma isn’t in pain anymore. I’m grateful for the memories I can carry forward of her and that I had her for so long. I am grateful for her laugh and her style. I’m glad to have some of her things and maybe one day pass them down.

I closed the book. I felt better—and then I panicked. I worried it was too soon to frame things in this way, that maybe I was using gratitude to bypass or deny the pain I was in.

But I also knew there had been stark contrasts even in the days immediately following her death, moments when I’d make a joke and feel totally normal and forget my suffering. That was surprising to me—learning that grief, while overwhelming, didn’t preclude me from doing everyday things like checking email or enjoying a moment outside.

I’d always come back to the pain, though. I would suddenly remember: Everything feels the same, but it is not. I’m a girl teaching myself to remember I don’t have a grandma anymore. For 36 years, I did, and now I don’t. I used to, but I don’t anymore.

I was teaching myself something new, something very painful, but the world kept turning, bringing with it things that caught my attention, momentarily pulling me out of my pain and into pleasure.

*

I’d played around with different gratitude rituals before, but my consistent practice began in 2018. That year, I sent my best friend Jess a text, demanding that she start sending me at least ten things she was grateful for—every day, no questions asked, no excuses.

The text wasn’t without context. We’d been talking about how she wanted to effect great changes in her life across different areas, and that made me think about the powerful jolt I’d experienced when I sat down to catalog the good things that happened on any given day. I thought her starting a similar practice could shift her energy and hold her accountable.

It wasn’t the first time I’d floated the idea to her, but on that April day in 2018, she followed through. Her gratitude list appeared in my email inbox that evening—and the day after that, and after that. After the first few emails, I began sending my own in response. For well over a year, we sent emails back and forth, detailing the big and the mundane, sharing what we were happy about each day.

We initially both saw powerful changes arise in our lives. She left the security of her long-term job without a real plan. I started to recognize the lack of self-love and compassion I had, and I took steps to remedy that. She addressed long standing insecurities and took first small, and then larger, movement toward believing in love and standing up for what she deserved.

We often mused about the possibility that it was the gratitude lists that in fact spurred us on as we made changes. We wondered how much of the openness and bravery we owed to the fact that each and every day, we actively chose to sit for a few moments and reflect on why we were thankful. But also: How could something so simple yield such powerful results?

Science tells us repeatedly that gratitude is good for us, but it’s one thing to read a study and another thing to experience it firsthand. Trading lists with Jess first taught me to really notice, to pay attention to my life, for more than just a moment or two of mindfulness.

I started to see the standout moments more easily: The smile on a stranger’s face when you pass them on a street, the dewdrops on the flowers you pass on your morning walk, the sound of your grandmother laughing on the phone halfway across the country—tiny miracles, really.

By the time lockdown started, Jess and I had outgrown our mutual gratitude practice. We revived it briefly during the pandemic to stay grounded, but for the most part, the last couple of years I’ve kept up with it on my own. Sitting down to chart what I’m grateful for each evening has been a balm when things are rough, an anchor holding me in place when things seem out of my control. Even on a bad day, I can usually think of at least a handful of things that brought me joy, however fleeting. This reminds me that both the good and the bad are all part of our human experience.

We are hardwired and conditioned to focus on the negative aspects of life for biological survival, but what it takes to survive emotionally in this (sometimes) long life is resilience. Gratitude is one way I build that up. And I understood now that going forward, I could use gratitude to honor both the time I spent with my grandmother and the opportunity I had to deepen our relationship during the pandemic.

*

As I finish writing this, it’s been a little over a month that I have been learning to say I am a girl who used to have a grandma. After a few weeks of grieving, I left that small town, the one right up the highway from my grandparents, and drove to New Orleans, the city I’ve lived in the longest as an adult.

I’d planned this visit before she died, but I ended up needing it more than I could’ve known then. I needed to be one of the only places that ever felt like home to me, after losing one of the rare people who also made me feel that way.

I got to the city and checked into the house I’m staying in. I walked down the side alley and was met with a wall of plants. I came around the corner into a lush yard full of trees and flowers, and my heart squeezed. I couldn’t help but think about how much she would’ve loved it here.

I walked inside and opened the French doors and stared out at the blooming trees. I felt a tiny space open up in my heart, and I took a picture to remember the moment.

Julia Cameron says in The Artist’s Way, “Survival lives in sanity, and sanity lies in paying attention.” I want to keep paying attention, even when it’s hard. Even when it feels like it’s going to break my heart. The everyday beauty, the living things around me, the infinitesimal things that usually go by unnoticed—noticing these are how I can continue on, how I take my next breath when this one feels weighted and heavy in my throat.

Today I got up and I went to the coffee shop down the street. I bought a homemade oatmeal creme pie and an iced oatmilk chai. I brought them home, and I put on a song I love and ate the entire pie. Now I’m sitting at the kitchen table, once again looking out onto that yard full of trees and flowering things—a yard she’ll never get to see.

I am thinking about her and how I can possibly do her memory justice through my words. I hope I have.

In another few weeks I’ll return home to Texas, to a physical space empty of life save for the flowers I potted and kept for myself, the ones she bought right before she died. She’s still right up the highway from that house, except now she’s at the sprawling veterans cemetery.

I will go visit her gravesite and tell her that I love her and that I’ve been thinking of her. Then I will pack up my things and those same flowers and move to a new city and embark on a new chapter of my life, as a girl without a grandmother.

I will think about her often, and when it hurts like it does right now, I will remember that it’s only painful because it was once so good, and then, I will try to feel grateful again.

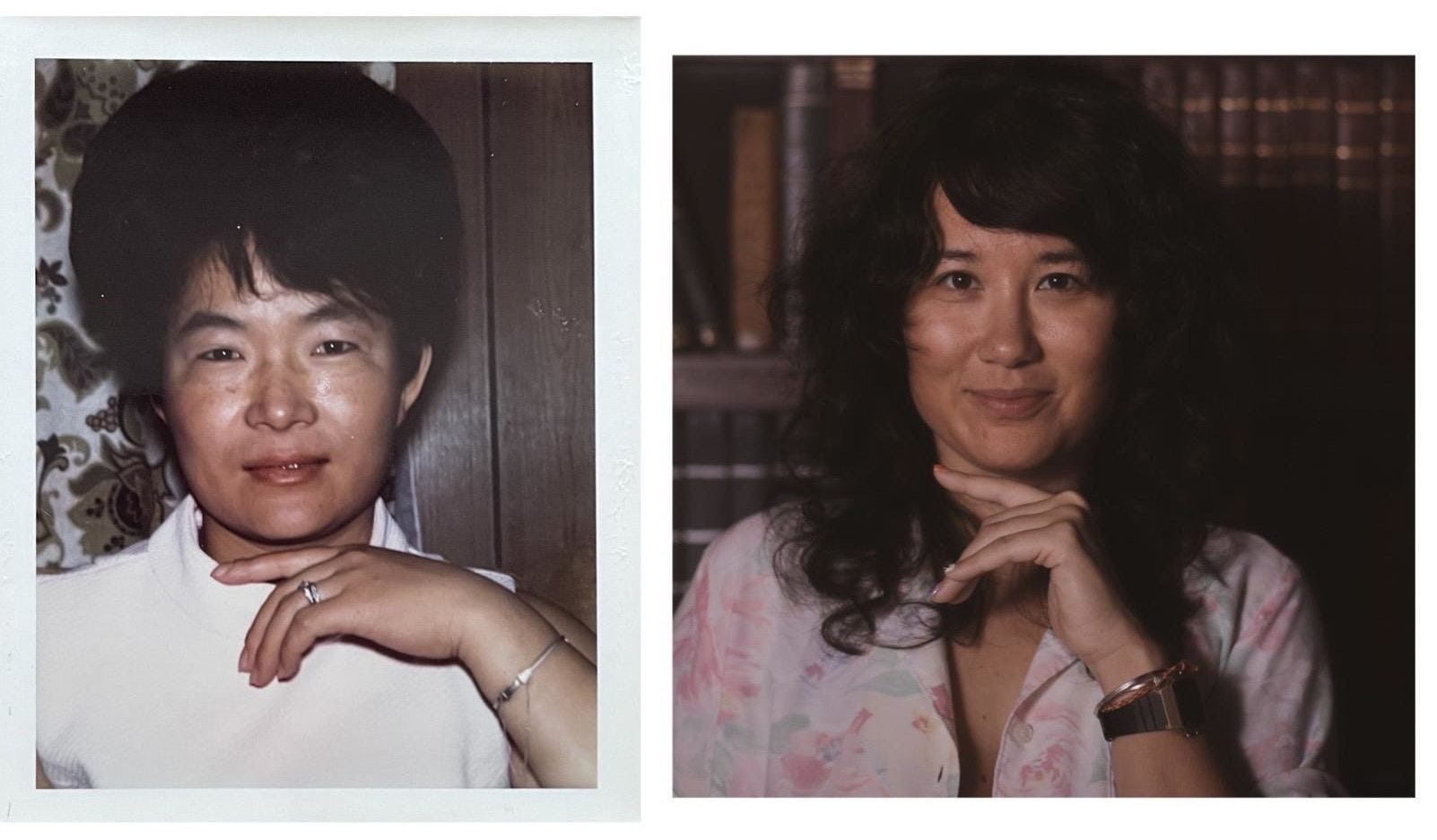

Photography of flowers and the author by Todd Taylor.

Nikki Carter is an experienced writer-editor-strategist who has been freelancing for over a decade. She's written under her own byline on topics like personal growth, sobriety, and work/life balance and been published on Business Insider, The Muse, Skillshare, and more. She's also created content for clients in healthcare, tech, and other industries. She runs a weekly newsletter, Will & Way, for Women of Color and is querying her first novel for publication. When she isn't writing, you can find her hiking, reading, or drinking tea and daydreaming.

Discover more from Nikki Carter.