Late one night in 2011 I attended a reading by W. S. Merwin. At the time he was the Poet Laureate of the United States and 83 years old. I was a senior in high school and, though I had only known he existed for one week, already zealous about his genius.

Though he quietly read a few poems, he spent most of his time in an unexpected, somewhat peevish digression on ‘influence.’ I don’t remember quite what he said, but I remember that the word – “influence” – fascinated and bothered him. A New Yorker piece from 2017 expresses the same theme: “After escaping the anxiety of influence, the poet discovered a brilliant, elemental poetry.” I wondered: why does influence make him anxious?

When Merwin’s reading ended, I drove home with two friends from school. I do not remember why, but we began discussing abortion. One girl, Mary, described a presentation she had attended at Sunday school the week previous. It rattled her. “I never thought it was murder,” she said, turning to look at me from the passenger seat, “until I saw those pictures. I never realized it was a baby. I never knew what they were doing.” I remember thinking: They’ve brainwashed her.

Or, somebody else’s influence had informed, even created, her thoughts. Only later did I start to wonder whose influence had made mine.

It is in the nature of an education to fill empty heads with new things. Everybody agrees that only some things can be used. The problem is which. Such disputes are at the core of the Scopes Trial, the 1619 Project, Galileo’s challenge to the church, Mao’s reeducation camps.

Education may be perennially controversial because the young are so easily misled. All thoughts being to them rather new, they have a difficult time parsing the stale or noxious from the genuinely bright and good. While you are probably never more like yourself (your true self; your honest self) than when you are a child, you are also never more sponge-like, never more likely to parrot what you hear.

In that car, when I was seventeen, I called Mary, also seventeen, ‘brainwashed’. I thought this because I watched The Daily Show with Jon Stewart every day, and he was pro-choice. At the time I did not realize that I tailored my opinions to fit his mind. I only realized this after college, when I met a young man studying in Edinburgh.

This young man was from Syria and had strong views about American foreign policy. These were sarcastic, biting, and, to my mind, contradictory: America should never have gone into Libya. American should never have gone into Iraq. America must go into Syria. How are they different? I wanted to know. They are, he assured me. He supported this with a few sardonic assertions about the American public and, to my surprise, began citing The Daily Show – now hosted by Trevor Noah. He said he watched Noah every day. Noah’s opinions on American stupidity were, it seemed, conclusive.

While I wanted to dismiss that young man for asserting ideas from another person, I had done the same to Mary. ‘She’s brainwashed,’ I had thought. But why? It wasn’t her idea, true. But it wasn’t my idea, either. It was a combination of influences, resulting in a worldview. For her, the Catholic Church. For me, Jon Stewart. Neither of us knew anything about abortion. I imagine we still don’t.

We borrow opinions every day from our friend, our parent, the neighbor, a teacher, a paper, a news anchor, the culture. Which is why even insane assertions can acquire the inertia of fact – such as when a Moroccan cab driver turned to me in Scotland to say, “Well, don’t you think it’s funny that Jews have so much money?” You have to do some heavy intellectual borrowing to arrive at a conclusion rooted in fantasy. I can think of a few more such fantastic conclusions widely held today.

If most thoughts are second-hand, then new ideas are rare. A young thinker opens a book in the library and says, Egads! I just spent a lot of time cooking up this idea. But look, it’s right here, on page two hundred fourteen, penned by a dead poet in Florence. Probably that poet in Florence stole the idea from someplace older, like a fairy story or the Bible. Likely Merwin stole it from him and, unwittingly, I echoed Merwin. Such is the overwhelming influence of influence. Examining it dispels our illusion of individuality, progress, or self-control.

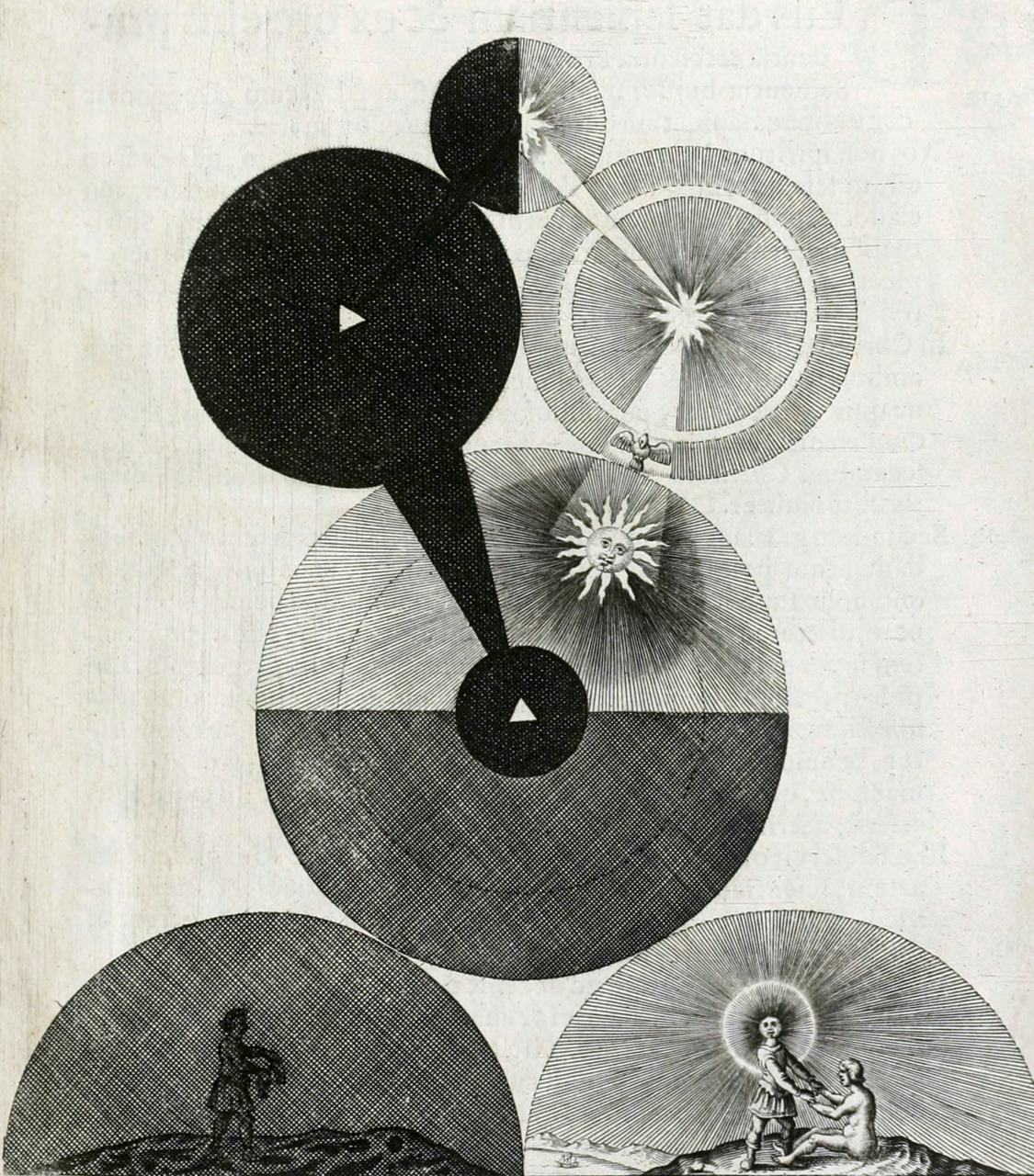

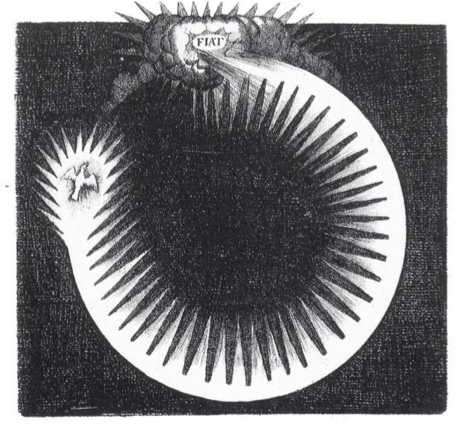

Before the European Enlightenment, it was believed that your life was determined by your birth position with respect to the stars. Al-Kindi, an Arabic scholar in the 9th century, described how light rays were a material that shaped the nature of the people on whom they fell, as a river shapes a rock. Five hundred years later, and Europeans were diligently crafting tin and agate glass talismans imprinted with the image of the Roman God Mercury, burying them in the earth near the houses of people they wished to ‘influence.’ Material emanations would pulse from the talisman, as they did from the sun. The word “influence,” from the Latin “to flow, to pour,” developed in the 1300s in tandem with this worldview to mean “emanation from the stars that acts upon one’s character and destiny.”

It is a beautiful thought, that even when I cannot see the stars, the light they shed on me is meaningful. Whether you agree the stars have this influence (you won’t if you’re a Capricorn), you will accede to the subtle material influence of our environment. From the factory’s shedding of particulate matter to the air’s proportion of ozone, things invisible to the eye impact health, development, and personality every day.

There is also the influence of what we see. Psychologist Albert Bandura’s “Bobo Doll experiments” demonstrated that children exposed to violence are more likely to repeat it. But influence is subtler, too. The woman carrying her laptop to work; the newly-erected medical school; the homeless man with his overturned hat and cardboard sign. Or perhaps, where you live, you see the man sweeping the courtyard of the temple; the woman carrying her child to the river; the alms-beggar in a holy city. They all inform what we believe to be possible, paradigmatic. How does a woman spend her time: with a briefcase, or a baby?

In the Middle Ages, cosmic influence was inescapable. Yet people could also manipulate these stellar rays, if only the appropriate coherence of image and word were found and bound into some material. Thus medievals could pull the levers of the universe. That was “magic.”

We like to think we have evolved beyond the Dark Ages, but our debates over “nature” or “nurture” pit destiny and agency against each other once again. One gains the upper hand, then crashes before the gods of sociology, neuroscience, psychiatry, the latest discipline tasked with explaining all human behavior. One day our psyche is composed of Freudian archetypes. Another day we are widgets produced by impersonal systems. Another day our personality is the product of our genes or epigenes or the color of the sky last Wednesday. If anything, today’s obsession with identity leads our social thought toward fatalism.

No wonder people are returning to astrology. If I can be influenced by a childhood trauma or sublimated death wish or the percentage of fluorocarbons in my drinking water, how can planets be irrelevant? There are only twelve Zodiac signs. Whereas there are millions of zip codes, a hundred million particles affecting my development, a thousand million epigenetic combinations that might determine the expression of my genes. So astrology, though silly, is at least uniting. Even beautiful. All that stuff in my head, including trivia about The Bachelor, may derive from the stars.

And it is easy. It is easy to put the ownership of our thoughts onto somebody else’s shoulders. Our carbon is recycled, our fluoride second-hand, why not our ideas and opinions, too? Since influence is omnipresent, we cannot really expect everybody to author all their thoughts, all their opinions. Then most of us would have nothing to say.

We are incentivized not to mention the soup of second-hand information that we willingly drink. We question others in this behavior but not seriously, because to seriously question something is to ask the same question of yourself. By our own acceptance of influence, we relieve each other of life’s most important and dangerous task: swimming through its endless effluvia toward the source. It is a job for adventurers, eccentrics, the pathologically curious. To confront our own thoughts may be as obliterating as coming face-to-face with a star.

‘Influencer’ is now a marketing term. It means a person on social media whose authority shifts the economic decisions of users who follow her account. The mystical valence of ‘influence’ is appropriate. That Kim Kardashian can persuade thousands of strangers to buy a particular colon-cleansing treatment is outside the realm of anybody’s powers of reason.

Coercion is now a crucial component of the word. Advertising relies on influencers to exploit. Shadowy figures hold “influence” in politics, indicating some undemocratic alliance of relationships, authority, and charm. When somebody has “influence” over you, it suggests they possess a dossier of damning information, or the dark arts of a hypnotist.

As the sun seems brighter by its rays, so ‘influence’ makes the human who possesses it bigger, brighter; it extends them beyond their body. Like light, it is a form of power, and it acts over a distance.

To the four fundamental forces of physics, I would add a fifth force, a human one: influence. As planets exert force in tension with other forces to arrange our solar system, so humans by their influence over space and time subtly rearrange one another. Invisible and immaterial as this human force is, it can pass light-like through our heads and into us, shaping our thoughts. It is not the kind of thing that you can avoid, any more than you can avoid gravity or magnetism.

Since sources of influence diminish and augment with every generation and human life, our human world is not that austere mobile of celestial spheres we see today. Rather, we live as the young universe did in that tumultuous zoo of creative destruction: the Big Bang. The constancy of such flux almost obscures any role we play in the arrangement of our world.

The medievals perceived, dimly and strangely, an escape from influence’s pressure. We may not have much control over ourselves. Yet over others our control is significant. My talisman of choice may be a poem, a song, a surgery. It may, buried in the right place, near the right person, influence the universe. It is a humbling, powerful thought. I’m sure they borrowed it from somebody else.

Sketches by Robert Fludd (1574 -1637).

Claire Ashmead-Meers is from Cleveland, Ohio. She graduated from Princeton in 2017 with a Bachelor's degree in History, Creative Writing, and Chinese Language, and in 2018 obtained a Master's in Fiction from the University of Edinburgh. She lives in Ann Arbor where she studies medicine at the University of Michigan. Her guiding spiritual principles come from Protestant Christianity, Zen Buddhism, and writers like Dostoyevsky and George Saunders.

Discover more from Claire Ashmead-Meers.